Dappled Things at the End of a World

On the Next Twenty Years of Dappled Things

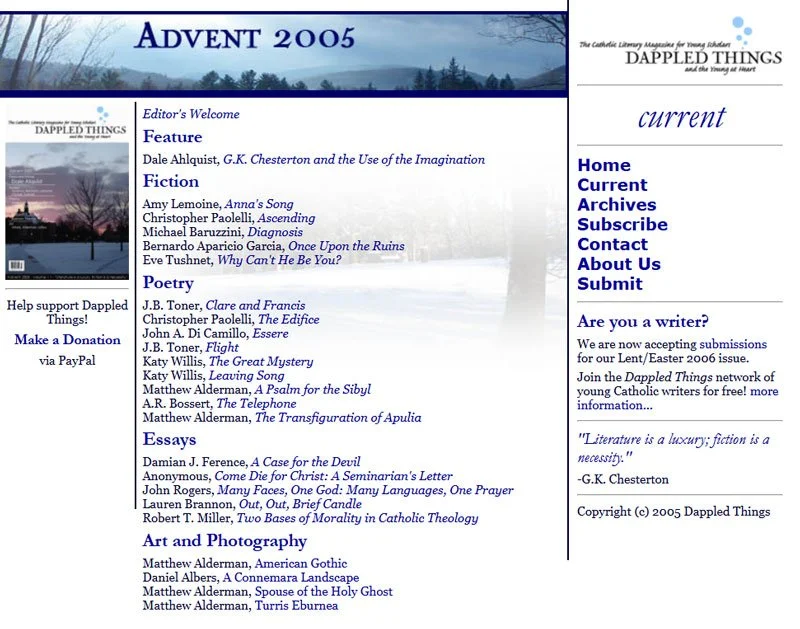

Our first online issue, released Dec. 18, 2005

This December marks twenty years since the release of Dappled Things’ first issue, in which we began our quixotic adventure to help bring Catholic art and literature back to life. It was an online-only edition that was admittedly rough around the edges, yet looking back on it, I’m struck by the proportion of names among its contributors that have since left a mark on Catholic culture. Among them are Dale Ahlquist, whose Chesterton Schools Network has revolutionized Catholic education; John DiCamillo, now president of the National Catholic Bioethics Center; Matthew Alderman, whose designs have brought beauty back to sacred architecture; and of course a variety of writers who have made their names across different genres, including Fr. Damian Ference, Eve Tushnet, and one young Katy Willis. Better known to our readers as Katy Carl, our longtime editor-in-chief, she is now an award-winning novelist and a leading figure in today’s Catholic literary renaissance, nurturing writers at the first Catholic MFA program in the country and helping new works come to light as editor of Luminor, Word on Fire’s literary imprint. It was an auspicious beginning that I can only attribute to the will of Providence, especially considering this penniless journal was published by a group of kids who were either still in college or barely out of it.

Quixotic, it was—the whole endeavor. Yet here we are twenty years later, with no lesser a figure than Dana Gioia recently declaring that, someway or another, Catholic literature has become vital again.

So what is our calling for the following two decades?

Twenty years ago, we set out to fight for the future of Catholic culture. We must, of course, continue on that same path. Yet twenty years ago, no one wondered whether writers and artists would soon be replaced by machines. The word “slop” mainly referred to bad food, and although YouTube had been founded just a few months earlier, we didn’t have to drown in a tsunami of “content” to find works of true beauty. These developments spur us to dream bigger, aim higher. We must continue to fight for excellence in Catholic culture, but we must understand that doing so now constitutes a struggle for human culture at large.

In recent years, I have often remarked to my wife that we seem to be living through some sort of endgame. We need not conclude that it is the end of the world to realize that we are witnessing the end of a world. Since Francis Bacon, Western civilization has turned from the pursuit of wisdom and Divine truth to the worship of power, understood as the technological conquest of nature—including human nature. “You will be like God,” the serpent said, and it seemed good to us.

Machines and Meaning

Paul Kingsnorth has summed up the civilizational path we have been walking for centuries now as an attempt to create a machine that can replace God. Yet the more we act as little gods, the more our societies have sunk into a crisis of meaning. If ever it was obvious that man does not live by bread alone, that time is now.

Storytellers, from the inspired writer of Genesis down to J.R.R. Tolkien in his account of the fall of Númenor, have repeatedly warned us against this core temptation. Now, with the rise of AI, the ambition to be as gods—not by forming our lives according to God’s will but by using force to grasp at our desires—is now spoken about openly by people in power. The transhumanist Ray Kurzweil, who is also a high-ranking Google executive, is (in)famous for his answer when asked whether God exists: “I would say: not yet.” More recently, he made headlines by predicting that humans will achieve a tech-driven immortality by 2030.

A Slop Apocalypse?

Leaving aside the likelihood of that prediction, it should seem eerily familiar to anyone who has read Tolkien’s account of the fall of Númenor, in which an advanced human civilization falls to the worship of evil in hopes of attaining immortality. This idolatry first creeps in quietly, then boldly, until being deceived by their former enemy, Sauron, the Númenoreans try to wrest immortality from the gods by force. In the end, the great civilization of Númenor sinks under a tidal wave, with only a remnant of faithful Númenoreans surviving to found the kingdoms of Gondor and Arnor, which are familiar to all who have read The Lord of the Rings.

Our culture, in farcical imitation of Númenor, is likewise grasping for immortality, but the wave that most immediately threatens to quash it is a tsunami of AI slop. The wave is just beginning to rise, but already about half of new articles on the internet are AI-generated, according to a new report from Axios. As it does so, two developments are likely. First, truly human art will become all the more precious, and more people will explicitly look for it. Second, it will become ever harder to find.

A Haven for Human Culture

So we return to the question of DT’s calling in the coming decades. We are absolutely committed to Catholic culture—to art and literature that grow out of the heart of the Church, out of the riches of the Catholic tradition—and that means we are committed to human culture. As the slop-wave rises, Dappled Things will be a haven for human art and literature. Just as our journal went to print when everyone was going digital, so will we double down on humanity as the herd goes to the robots. This will be a place to reliably find art and literature made by someone with a soul, and where work is curated, edited, and published by a team of inefficient, beautiful humans.

Of course, we can only do that with your help. For our twentieth anniversary, we have set a goal of raising $20,000, an amount of support that is crucial to continue our work. Will you stand with us for Catholic, human culture? Not everyone understands the importance of this mission, so please consider what you can give and support Dappled Things today, whether your gift is $5,000 or $50.

Yes, to fight for human art seems today as quixotic as anything, but we know all things are possible with God. And in any case, it’s the kind of goal we have experience pursuing.

Yours in Christ,

Bernardo Aparicio García

Publisher

Dappled Things