Damned Beautiful Things: A Conversation

Joshua Hren and Lee Oser

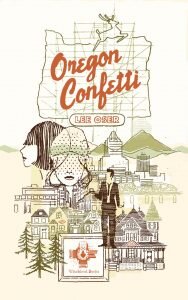

Editor’s Note: Dappled Things is pleased to have the opportunity to share this wide-ranging dialogue between Joshua Hren, editor in chief of Wiseblood Books as well as an associate editor of Dappled Things, and Lee Oser, author of the novel Oregon Confetti, published by Wiseblood Books in November 2017.

Joshua Hren: In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s self-interview, he notes: “My idea is always to reach my generation. The wise writer, I think, writes for the youth of his own generation, the critic of the next and the schoolmasters of ever afterward. Granted the ability to improve what he imitates in the way of style, to choose from his own interpretation of the experiences around him what constitutes material, and we get the first-water genius.” Walter Ong argues that the writer’s audience is always a fiction. Still, it seems wise to give that fiction some criterion, some broad groupings. Would you say that you aim to write for the same three categories Fitzgerald identifies, or do you imagine your audience differently—and if so, why so?

Lee Oser: My situation is different, though. I was born in 1958, towards the end of the baby-boomer generation, and I had to learn to see through their ubiquitous “youth culture.” They had very good music, but almost nothing in literature. It was Tolkien who filled their literary void, and that void remains. So I write satire, and I write comically in exile, defiance, and bitterness of heart. My intended audience has always been my students who see through the generational fiasco that was and is the Boomers: how they have confused politics and civilization, how they never understood the nature of sex or children or family, their unwittingly hilarious claim to be rebels, their suburban experimentation with God, as if God were another drug or a visit to a fast-food restaurant. So I had to escape these eternal adolescents and look for grown-ups in the next generation. It is a sweeping condemnation, but a thinking person must deal in general truths, if only to stay sane. So I write for the grown-ups in the next generation. At least there are some.

By the way, do you know the Pat Hobby stories? It was Ralph McInerny’s staunch defense of those stories in particular and of Fitzgerald as a Catholic writer in general that clued me in.

JH: Claiming Fitzgerald as a “Catholic writer” in the sense that term is typically used is a tall task, no? In hisHemingway’s Dark Night: Catholic Influences and Intertextualities in the Work of Ernest Hemingway, Matthew Nickel has conducted an exhaustive defense of Hemingway as haunted by Catholicism. Some have made a similar argument concerning Jack Kerouac—especially his Visions of Gerard. In what sense is Fitzgerald’s work “Catholic,” and how is this different from and similar to other writers, such as Kerouac and Hemingway, who are haunted by Catholicism?

LO: Our larger picture of Catholic writers is changing as the written word cheapens in value, as art blurs into groupthink, sexuality withers into sterility, and as the soulful element of a Fitzgerald is eclipsed by materialism and the diabolic will to power. Catholic soulfulness is expressed in fiction through the force of conscience, not through the cooler, more existentially objective mode of writing that distinguishes Hemingway. I cannot speak for Kerouac. If pushed, I would say that Fitzgerald’s conscience was Catholic. So was his idea of the human person.

JH: You mention Fitzgerald’s Catholic conscience, which is to say that it was more than a nostalgia for incense and votive candles playing out like old reels in the back of his mind. What you are saying, it seems, is that this Catholic conscience was a sort of hard kneeler on which he reposed as his senses and mind reached out to capture the flappers and philosophers, the Stock Market Crash and the car crash—that all of this played out under more than the watchful eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg. In the notes he left for the unfinished novel The Love of the Last Tycoon, Fitzgerald wrote “action is character.” And yet if you are correct, might we say that character is driven by conscience, or that action is registered according to the lights of various characters’ consciences? If this is true, although his prose was beautiful, you seem to suggest that in fiction he was doing much more than telling moving stories that keep readers rapt to this day. Many cringe at the moral character of fiction. Consider, for instance, Sherwood Anderson, who said that “There was a notion that ran through all story-telling in America, that stories must be built about a plot and that absurd Anglo-Saxon notion that they must point a moral, uplift the people, make better citizens, etc.” In what sense is Anderson’s resistance to “morality tales” legitimate, and it what sense is the moral dimension part of the artistry of the story? How does conscience correlate with the cosmos of your fiction?

LO: You have to pay attention to the choices that confront a writer, especially when he or she takes on the subject of man and woman. Fitzgerald is always superbly tactful, and his tact is informed by a depth of morality that is Catholic. Sexuality is sacred to him. His cosmos is sexed. He has the right taboos. And he was chivalrous, even in Hollywood—all while avoiding cheap consolations, cheap nostalgia, and general phoniness. As for Anderson’s comment, I have always preferred stories with plots, and I became a novelist when I learned to write them. Moral uplift, on the other hand, is a great way to discourage boys from reading and very popular in education right now. Conscience for me is a kind of sulfur-detector, though usually I require a bit of hell to get the machine working. You will recall Nietzsche’s rather civilized laughter at the Kantian notion of the artist’s disinterested interestedness.

JH: In “Taking Things as They Are,” your review of Myles Connolly’s novel Mr. Blue, you argue that “it is really Newman who offers the most valuable philosophical remarks about Catholicism and literature: ‘We must take things as they are, if we take them at all . . . we Catholics, without consciousness and without offense, are ever repeating the half sentences of dissolute playwrights and heretical partisans and preachers. So tyrannous is the literature of a nation; it is too much for us.” There is no stronger warning voice against the tendency toward dual or double standards than Newman’s in his lecture “English Catholic Literature.” Newman grasped the crucial relation between history and consciousness. So too did Chesterton. Elsewhere in The Idea of a University, Newman warns us against taking man “for what he is not, for something more divine and sacred, for man regenerate.” He cautions us to “beware of showing God’s grace and its work at such disadvantage as to make the few whom it has thoroughly influenced compete in intellect with the vast multitude who either have it not, or use it ill.” But doesn’t Newman’s idea of literature as “Record of Man in Rebellion,” his insistence upon “taking things as they are,” inhibit us from literary representation of the actions of grace? Surely grace is not beyond literary representation? Doesn’t the record of man’s sinfulness, lest it remain a Hobbesian or Calvinistic documentation not merely of sinfulness but of an unreal, hyperbolic depravity, also beg to become the record of grace built upon that sinful being?

LO: As you say, grace is not beyond literary representation. But if you are not extremely wary as a writer, grace has the power of any great cliché to expose you as a fake. Christian critics fall into a similar trap, for instance, praising T.S. Eliot for his humility when they should be noticing how he avoids turning humility into a cliché, how he escapes the avalanche of clichés about humility. O’Connor handles the problem of grace miraculously well in “The Artificial Nigger.” You can see what a hard problem it is by reading that story, one of her best. Conversion stories pose similar difficulties: there’s nothing harder than to write a moving conversion story for grown-ups.

JH: Flannery O’Connor, whom I will try not to circle like a rhinoceros beetle around a Georgian porch light, noted that “The woods are full of regional writers and it is the horror of every serious Southern writer that he will become one.” Still, in spite of her reservations, she said that the South had given her fiction “its idiom and its rich and strained social getup.” You are not a “regional writer,” unless we are going to consider that patch of land from sea to shining sea a “region.” The action of your last novel, The Oracles Fell Silent, mostly happens on Long Island. This time you’ve switched coasts. As the title of your latest novel signals, Oregon Confetti takes place in the Pacific Northwest, most of the action unfolding in or around Portland. Television shows like Portlandia have tried to capture the “idiom” of that place, and I suppose some count David James Duncan (author of The Brothers K) and Annie Dillard as regional writers probing the Pacific Northwest. In what sense is Oregon Confetti a “regional novel”? What idiom, and what rich and strained social getup does the story absorb from the peculiar character of Portland, and why would you set the novel amidst these particular realities?

LO: I arrived in Portland when I was twenty, a college drop-out, young enough that things still made a lasting impression. It is a beautiful part of the country. For a time, I drove a Pronto car and learned the town pretty much by heart. The bands I played in gigged all over the place. I met a lot of interesting, artsy people, including a self-possessed woman who owned a local gallery and a dark exotic woman who worked in one. All that gets into Oregon Confetti, whose main character is an art dealer of sorts. My Portland is more imaginative than regional, more emotional and associative than factual. I know “Portland writers,” career writers with local magazines and college jobs, but it was never my scene. Portland for me keeps shifting and layering, and I like how the present-day town arranges itself over the palimpsest. Right now, it seems a strain of secular political insanity is overrunning the streets, pushing out the civilized virtues, and that attracts me as a subject of satire.

JH: In Culture of Narcissism, Christopher Lasch insists that we “prefer art that at least overtly imitates something other than its own processes,” that doesn’t constantly proclaim “Don’t forget I’m an artifice!” Lasch singles out the writing of John Barth, who in the course of writing his story “Chimera” notes that “Storytelling isn’t my cup of wine; isn’t somebody’s; my plot doesn’t rise and fall in meaningful stages but . . . digresses, retreats, hesitates, etc.” Morris Dickstein observes that the “emotional withdrawal” of such writing threatens to disintegrate into catatonia. Writers give up on the quest to master or imitate reality, and instead retreat into superficial self-analysis which smothers the deep subjectivity “that enables the imagination to take wing . . . His incursions into the self are as hollow as his excursus into the world.” Oregon Confetti could have fallen into the traps of metafiction, fiction about the fictionality of fiction, or the artificiality of art. And to some degree it does deal with these things. After all, the protagonist, Devin, is an art dealer. Further, a major subplot of the novel involves the bartender Clarence, who holds forth at Sibyl’s Chop House, working out his novels in part by trying them out on the pub’s patrons. We read that “He’d absorbed thousands of plots and sub-plots, he’d studied twists and turns beyond count, he’d hobnobbed and tippled with the best of them, but his work remained stubbornly his own. It was his own curious fusion, with its inviolable laws, its proportions and symmetries, its parts and its mystical unity, all of which was more important to him than what others had to say about it.” In addition, at one point Devin comes across a “a medieval suit of armor apparently airing itself on the sidewalk. It rose from a bronze plinth and its open visor accommodated a miniature TV screen.” I simply must quote the novel’s description at length:

Upon inspection, the screen was seen to display the fight scene between Iron Man and Ultron in a bit of Hollywood fluff called Avengers: Age of Ultron. A lithium battery, soldered onto the armor’s breastplate, ensured that the half-minute scene would repeat itself, electronic blink after blink, for a decade or more. I knew this vulgar contraption perfectly well because I’d paid for it. It was made by a follower of the late Nam June Paik, an art student at UCLA who in a fit of poetic inspiration had named it “Iron Man.” The armor came from a sale at the MGM lot in Hollywood. The whole shebang, or “video installation” as we say in the biz, cost me twenty-five hundred dollars and I was hoping to rake in 20K. Some elf or fairy seemed now to have transported it, possibly through a window, and placed a fanciful signboard in its glinting gauntlets. The sign announced FREE JUNK, and these words, meticulously drawn in golden uncials, were gloriously encircled by a shining silver laurel wreath. In the lower right, on a heraldic shield of checkerboard design, the initials OO appeared. I stood in awe, and then flew in a panic up the four flights of stairs to my shop.

In other words, you tackle the nature of storytelling and the distinction between art and trash directly in your novel. Why use literary art to critique or capture the nature of art, and how do you give these explorations breadth and depth, escaping the trappings of metafiction?

LO: The whole idea of metafiction is a very new name for a very old device. For instance, check out the description of the shield of Achilles in the Iliad, or look at the play within the play in Hamlet, or read Cervantes, or see Wordsworth’s dream of the Arab. Metafiction (if that’s the name we want) is central to The Thousand and One Nights. When metafiction passes into clever formalism and aesthetic pretension, then you get Dickstein’s “emotional withdrawal.” I am not emotionally withdrawn.

JH: In Luke Rhinehart’s novel The Dice Man, the protagonist is emblematic of a certain contemporary disillusionment with free will. He decides to renounce free choice with the same dramatic abandon that St. Francis denounced his clothmaker’s inheritance: “I established in my mind at that moment and for all time, the never-questioned principle that what the dice dictates, I will perform.” Of this capitulation Lasch writes, “Whereas earlier ages sought to substitute reason for arbitrary dictation both from without and within,” contemporary “man” seeks to “revive earlier forms of enslavement.” The problem of freedom is a major concern of Oregon Confetti. At least twice, characters address it explicitly, discursively. During a public lecture, as one of his Jesuit confreres snores so loudly that he almost drowns out the speaker’s points, the ancient priest Fr. Low responds to an attendee wondering whether man “is losing his free will in modernity.” Fr. Low replies with eminent judiciousness. “I see no reason,” he says, “why grace or freedom should be given equally to generations. But it’s not a matter of deduction. Non in dialectica complacuit Deo salvum facere populum suum! Now that I think of it, you also run into what we might call a self-fulfilling prophecy. Men and women who refuse grace deny their own freedom.” Later, at Sibyl’s Chop House, Clarence says that in terms of storytelling, “the main thing in my opinion is that a character make his or her choice freely, so as to reveal something of significance about his motives and how he thinks under certain circumstances, usually involving temptation.” A good story, he goes on, makes a number of very real prospects palatable, a number of scenarios which the character can choose. “Either way we learn something about him while having our own response tested.” To what extent do you think Lasch is right to see “contemporary man” as actively working to resuscitate earlier forms of enslavement in terms of fate and free will? Why is your novel preoccupied with freedom, and what did you find—any uncanny discoveries or epiphanies, for instance—as you probed the problem of free will through fiction?

LO: Chesterton says somewhere that when Aquinas defended free will he invented the lending library. A character in a novel has to face choices, has to exercise a modicum of freedom, and free will is always an expression of grace. Characters can confuse freedom and bondage. They can become enslaved. But to become enslaved is implicitly to suggest an alternative. At bottom, novels are theological, or else they are nonsense.

JH: Fitzgerald opened our conversation; as it’s almost Closing Time, I’ll let him lead us out the door as well. In the very first line of Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and the Damned, we read that the protagonist was in his early twenties when “irony, the Holy Ghost of this later day, had theoretically at least descended upon him. Irony was the final polish of the shoe, the ultimate dab of the clothes-brush, a sort of intellectual ‘There!’” The dominant cultural ethos of this world, in art as elsewhere, is irony, not Socratic irony, which aims to provoke the listener or dialogue partner toward truth, but cynical irony, a means of dealing with the dissolution and fragmentation of the world, of so many people’s disillusionment with the political, the religious, etc. through a wry grin that at best provides a momentary, and quite shallow, laugh. Again, instead of harnessing this irony in our favor, we should try to ask: what is behind the ironic impulse? I would suggest that at least part of what we will find behind the ironic impulse is a sort of self-protection against the hollowness of the world, against those that T.S. Eliot called “The Hollow Men”:

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

David Foster Wallace saw irony as the zeitgeist of our times, arguing that pervasive irony marks a “weary cynicism” which is essentially a mask to cover “gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naivete,” further calling this the “last true terrible sin in the theology of millennial America . . . what passes for hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human, since to be really human . . . is probably . . . to be in some basic interior way forever infantile.” Wallace, quoting Lewis Hyde, notes, “Irony has only emergency use. Carried over time, it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage.” This, Wallace notes, “is because irony, entertaining as it is, serves an exclusively negative function.” Its critical gaze is ground-clearing, but, we must ask, what is left when the ground is all cleared? Two questions for you, then.

First: Wallace concludes that it is inaccurate to claim that we have rejected all religious and moral principles, as the more radical nihilists of Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons espoused. In his essay on Dostoevsky, Wallace muses, “maybe it’s not true that we today are nihilists. At the very least we have devils we believe in. These include sentimentality, naivete, archaism, fanaticism. Maybe it’d be better to call our art’s culture one of congenital skepticism.” Do you share any of these “devils” as the targets of your own irony? Would you add any to the list, or take some off of it?

LO: I had a very interesting experience when I was a boy. I used to tell my little brother fairy tales that I made up in telling them. One story was about a castle haunted by the ghosts of whales. We loved these imaginative conceptions for their own sake. Now I see them in terms of sub-creation. But when I innovated, right about the time when puberty hit, and told a story about a soldier who struggles across a desert only to drop dead seconds before his would-be rescuers arrive, I thought I was discovering irony. I thought it was genius, but my brother hated it! Trying to define irony is a fool’s errand, if you ask me.

JH: Finally: You write satire, and you write comically. Does your selection of comedy have anything to do with the ironic spirit of our times? How do you reckon with the insufficiency of satire in and of itself, with the need to leave something good for the reader, to point somewhere after you have cleared

the ground?

LO: I have tried to include what literary critics call the frame or standard of the satire. I’ve tried to do so in two ways: first, by writing a book that distinguishes between art and junk and does so as a work of art (a typical humanist approach, going back to Erasmus); and then, by telling a love story. I am with Fitzgerald in that. The stuff between Devin and Agatha in the novel was by far the hardest to write. I was trying to reclaim some territory that has been lost and to give it new life.

Joshua Hren teaches and writes at the intersection of political philosophy and literature and of Christianity and culture. He serves as associate editor of Dappled Things and as editor in chief of Wiseblood Books. His scholarly work appears in such journals as LOGOS, poems in such journals as First Things, and short stories in a number of literary magazines. His first academic book, Middle-earth and the Return of the Common Good: J.R.R. Tolkien and Political Philosophy, is forthcoming in 2018, and his first collection of short stories, This Our Exile, is forthcoming through Angelico Press in November of 2017.

Lee Oser earned his doctorate in English at Yale in 1995. He taught at Yale and at Connecticut College and then moved to Holy Cross in 1998. He has published three well-received books of literary criticism. He is known for his efforts on behalf of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers (ALSCW), a literature-advocacy group based in Boston. He is the author of the novels Out of What Chaos, The Oracles Fell Silent, and Oregon Confetti.