Let us reverently marvel

Many years ago, I adopted a line from the forty-seventh chapter of Julian of Norwich’s Revelation of Divine Love as one of my guiding principles. A combination of multiple translations, I frequently remind myself that “the soul has two duties. One is to reverently marvel. The other is to humbly endure, ever rejoicing in God.” The first duty—to reverently marvel—speaks to the creative impulse. Why do people sketch miniatures, paint murals, take photographs, throw pottery, weave tapestries, and write poetry and novels? Why do we sing? Why do we compose nocturns, operettas, and symphonies? Why do we forge iron and blow our breath into molten glass? Isn’t it that we’ve been touched by something marvelous? That we’ve had a taste of something inexplicably transcendent and beautifully divine? And then? What do we do? What do we do with all that soul-moving, heart-filling, love-overflowing, other-worldly beauty that we’ve been invited to see? We create.

We create, not like God—who creates somethings out of nothing—but as witnesses and gatherers of the marvelous. We listen, watch, smell, touch, and taste the marvelous. We are full of the marvelous and are moved to share. We overflow. We must share with others the things we reverence.

Here, thankfully, the second duty of the soul comes to our rescue. Our next task is “to humbly endure.” We must work—day-by-day, little-by-little, moment-by-moment—on developing our craft. And why? Why this persevering and lowly discipleship in the face of something so wonderful? Without humility we are shooting stars and fleeting sparks who burn too quickly. With an enduring craft, we linger in the marvelous, “ever rejoicing in God.” We become steady lights and guiding lodestars that invite others to rejoice in God.

The world around us reveals God’s presence. When viewed with a sacramental imagination—with this reverent marveling—evidence of God’s love is abundant. In his Introduction to the Devout Life, St. Francis de Sales states that to that end, God “has given you an intellect to know him, memory to be mindful of him, will to love him, imagination to picture to yourself his benefits, eyes to see his wonderful works, [and] tongue to praise him.” With a sacramental imagination, the skepticism of “seeing is believing” is transformed. “Seeing” the wonders around us points us to belief. “Seeing” lets us know the handiwork of the Creator. “Seeing” lets us approach mystery and grace. We can also reverse the words in the phrase and consider that “believing is seeing.” When we know God as Divine Author, we see evidence of his authorship everywhere. Together, “seeing is believing” and “believing is seeing” work to make the abstract concrete, the universal specific, and the common delightful.

An epigraph in a 1917 edition of Norwich’s Revelation of Divine Love, edited by Grace Warrack, reads: “Truth seeth God, and Wisdom beholdeth God, and of these two cometh the third: that is a holy, marveling delight in God; which is Love.” The outpouring of this third item, this “holy, marveling delight” is the source of the sacramental imagination.

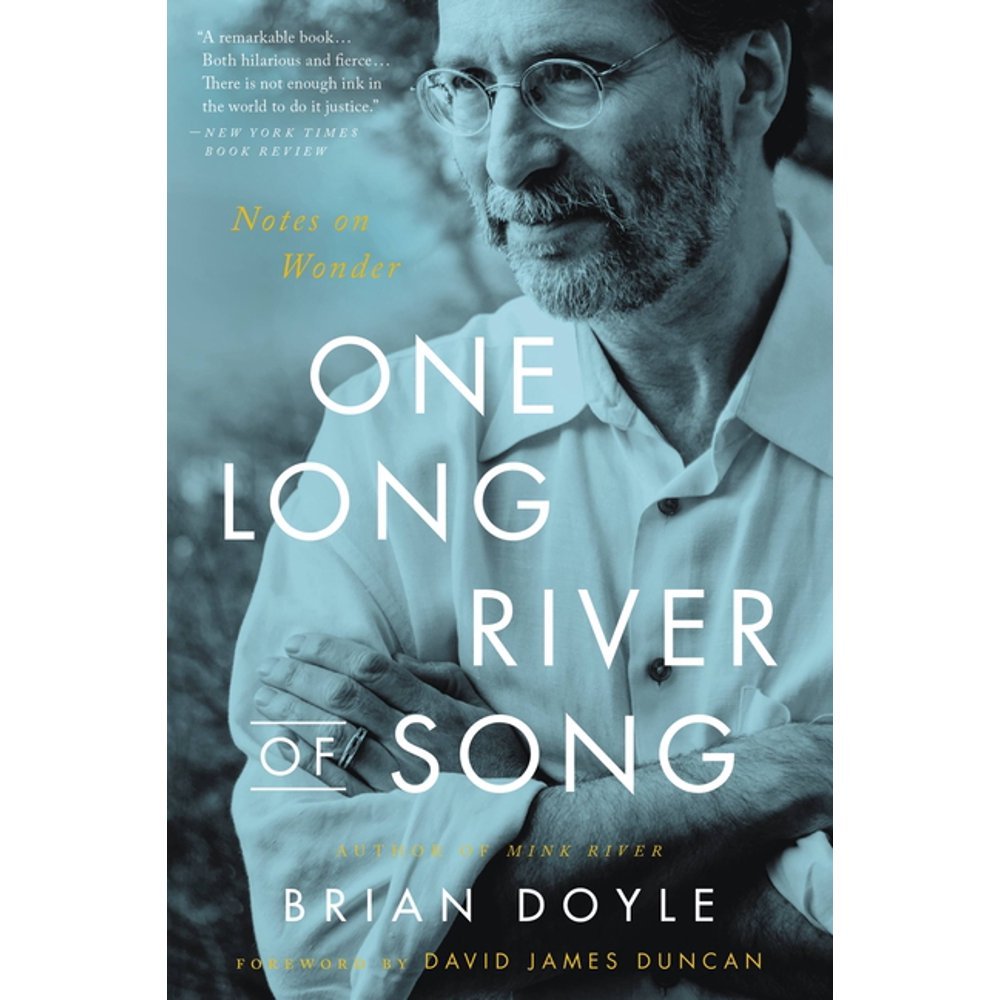

Speaking of an “outpouring,” this marveling delight is present in the essays, poetry, short stories, and novels of Brian Doyle (1956-2017). His style reveals a reverence for the inexhaustible wonder that surrounds any given idea. Consider three accolades for One Long River of Song, a collection of Brian Doyle essays. Mary Oliver states, “Doyle’s writing is driven by his passion for the human, touchable, daily life, and equally for the untouchable mystery of all else.” Anthony Doerr writes, Doyle’s “essays are the memories and thoughts of a man who made it his purpose in life to recognize kindness, humor, grace, and beauty wherever he saw it.” Lastly, the publisher writes, “Through Doyle’s eyes, nothing is dull. [This book] invites readers to experience joy and wonder in ordinary moments that become, under Doyle’s rapturous and exuberant gaze, extraordinary.” These accolades all describe the “marveling” quality of Doyle’s work.

At some point in each piece (many places in his longer works), Doyle’s exuberant descriptions inevitably reach a climax. His evenly paced narrative gathers speed and becomes descriptively expansive, often in the form of a paragraph-long sentence that holds a flurry of cataloging clauses and a string of unpunctuated adjectives. After his first novel was published, a brother sent him a page with nothing but commas and wrote, “you might want to learn to use these.” Despite this criticism, this technique persists throughout his works.

To get a sense of his distinct style, consider the following three excerpts from Mink River, his first novel. The first is a portion—yes, portion—of a sentence found early in the text:

and so many more stories, all changing by the minute, all swirling and braiding and weaving and spinning and stitching themselves one to another and to the stories of creatures in that place, both the quick sharp-eyed ones and the rooted green ones and the ones underground and the ones too small to see, and to stories that used to be here, and still are here in ways that you can sense sometimes if you listen with your belly, and the first green shoots of stories that will be told in years to come—so many stories braided and woven and interstitched and leading one to another like spider strands or synapses or creeks that you could listen patiently for a hundred years and never hardly catch more than shards and shreds of the incalculable ocean of stories just in this one town, not big, not small, bounded by four waters, in the hills, by the coast, end of May, first salmonberries just ripe.

In this next sentence, we are invited to imagine the clutter in Owen’s workshop:

Close your eyes for a minute and think of all the closets you have ever crammed with stuff, and all the basement workbenches asprawl with tools, and the shelves crowded with fishing gear and sports equipment and paintbrushes and furnace filters and nails and eyelets and grommets and washers and such, and merge them all in your mind, not haphazardly but with a general sense of order, a relaxed and affectionate organizational sense, such that you would have a pretty good rough idea where something might be if you needed to find it, and when you went to look for it you would find it in less than a minute, and even when something took more than a minute to find, you would find something else that you’d been looking for not desperately but assiduously; then think of all the rich dark male smells you have ever liked, the smells that remind you of your dad, your grandfather, your uncle, your older brother.

Later in the novel, we see No Horses, at work in her art studio:

Next day No Horses carves and chisels and whittles and slices and hammers and chips and snicks and shaves and slices the wooden man all the day and half the night and by that time there’s hardly any wooden man left at all, he’s mostly a pile of oak chips as high as her knees, and next day after that she starts all over again with a piece of spruce about as big as a goddamn car, as Owen mutters darkly after hauling and hefting the thing into the studio panting and swearing and cursing, and she works furiously all day and half the night making a new man, stopping only to run over to the doctor’s house to see Daniel every few hours, and she doesn’t stop to eat at all though Own comes twice by with sandwiches and coffee.

These long, exploring sentences walk us through the marvelous aspects of an idea, setting, or scene. We are invited to see that details—a very wide range of details—matter. Our sight is simultaneously zoomed in to the smallest details and zoomed out to larger contexts and relationships.

Doyle uses this cataloging technique thematically as well. In “Joyas Voladoras,” he starts by considering the hummingbird. He notes how often the hummingbird’s heart beats per second. He comments on the hummingbird’s size, its colors, its range, its behavior, its metabolism, and the numerous species of hummingbirds in existence. He next considers the mammal with the biggest heart: the blue whale, the size of its heart, its characteristics. Next, he contrasts birds and mammals with reptiles and fish. In the concluding paragraph he turns to the human heart. He writes,

So much held in a heart in a life. So much held in a heart in a day, an hour, a moment. […] You can brick up your heart as stout and tight and hard and cold and impregnable as you possibly can and down it comes in an instant, felled by a woman’s second glance, a child’s apple breath, the shatter of glass in the road, the words I have something to tell you, a cat with a broken spine dragging itself into the forest to die, the brush of your mother’s papery ancient hand in the thicket of your hair, the memory of your father’s voice early in the morning echoing from the kitchen where he is making pancakes for his children.

As readers, in an instant, our hearts are felled by this concluding sentence. We know falling in love. We know the love of parent and child. We know disaster and suspense. We know the hard truth of nature’s ways and of death. We all have detailed memories that we cherish.

Doyle continues his contemplation of the heart in the essay “Heartchitecture.” At the beginning of the first paragraph, he writes, “Let us contemplate, you and I, the bloody electric muscle. Let us consider it from every angle.” At the end of this paragraph, Doyle combines science and poetry when he asks us to look at “the sodium that is your soul, the potassium that is your personality, the calcium that is your character.” He discusses the function of arteries, veins, blood, and valves. He lists all that can physiologically go wrong with the heart. He talks about how the heart forms in utero. He drops the statistics that “the highest rate of death by failed heart is in Utah” and that “twenty percent of all babies born with flawed hearts will die before their first birthday.” At the essay’s conclusion, he writes,

Our body fluids contain about one percent salt, nowadays—very likely the exact salinity of whatever ancient sea we managed to crawl out of, a sea we could leave because we had learned, first of all, to contain it; and the sea is contained and remembered most crucially now in the heart, where salt sloshes back and forth between cells, forming the first thrum of the heartbeat, first hint of the absolute and necessary note from which comes the salt song of You.

This is Doyle at his cataloging best. In this essay, we travel through the scientific, biologic, human, and creative realms of the heart to arrive at “the salt song of You,” a reverent and celebratory look at the individual soul.

Doyle’s propensity to catalog also directed his inquisitiveness. In the essay “Being Brians,” we learn that Doyle contacted 215 other Brian Doyles living in the United States and asked them, “How did you get your name? What do you do for work? […] What’s your wife’s name?” Almost half of the Brians responded, and the essay highlights the varied replies. When asked about the essay by the editors of In Fact: The Best of Creative Nonfiction, Doyle states, “What please me about this piece is that it went off in unexpected direction and twists and turns, and it went deeper than I expected into the heart, and it was sometimes hilarious and sometimes sad, like life.”

Doyle handles sad moments with equal care and reverence. In “Leap,” Doyle focuses on a couple who “leaped from the South Tower, hand in hand” on September 11, 2001. True to his form, he catalogs what different witnesses saw and said as they struggled to understand the “pink mist in the air.” In “His Listening,” Doyle laments the fact that his father, who so patiently and generously listens to everyone, is losing his hearing and that he misses “the way he stared at your face as you spoke, with all his soul open and alert for your story.” In “Last Prayer,” when he knows he is dying, he thanks God for all his blessings. Often, during public recitations of his essays—there are several video compilations on YouTube—he tears up and struggles to maintain his composure. At the end of many of the recitations, he says “Amen.”

Many of Doyle’s essays discuss reading and writing. In “Selections from Letters and Comments on My Writing,” he lists a few of the highlights from letters he has received from readers. The comments include,

Why do you abuse punctuation? What has punctuation ever done to you? Where were you educated, if you were educated? Did you not study grammar? […] In your book about a vineyard you veer off every other chapter into whatever seems to be in your head at the time. Why did you publisher let that happen? […] Our class is studying your essay about hummingbirds and we do not understand the ending. Do you?

Here we see Doyle’s ability to “humbly endure” criticism and reader feedback with humor and light-heartedness and in “Review: Bin Laden’s Bald Spot & Other Stories, by Brian Doyle,” he humorously pans his own book. In all seriousness, in “How Did You Become a Writer,” Doyle writes, “The real reward is to be read; and if you get a letter in response, well, then, you have been paid in the most valuable of coins, the music of another heart.” Finally, with his eye on endurance, Doyle writes, “in the end, what have we to exchange that matters except stories of grace and courage, laughter and love.”

Brian Doyle’s work will make you laugh and cry and drop everything to send an email to your friends with the subject line: “MUST READ, check out this awesome essay!!!!!!” You will be delighted and charmed and mesmerized. Brian Doyle knew his readers. In “The Greatest Nature Essay Ever,” he writes,

It turns out that the perfect essay is quite short, it’s a lean taut thing, an arrow and not a cannon, and here at the end there’s a flash of humor, and a hint or tone or subtext of sadness, a touch of rue, you can’t quite put your finger on it but it’s there, a dark thread in the fabric, and there’s also a shot of espresso hope, hope against all odds and sense, but rivetingly there’s no call to arms, no clarion brassy trumpet blast, no website to which you are directed, no hint that you, yes you, should be ashamed of how much water you use or the car you drive or the fact that you just turned the thermostat up to seventy, or that you actually have not voted in the past two elections despite what you told the kids and the goat. Nor is there a rimshot ending, a bang, a last twist of the dagger. Oddly, sweetly, the essay just ends with a feeling eerily like a warm hand brushed against your cheek, and you sit there, near tears, smiling, and then you stand up. Changed.

Reading Doyle’s work will change you. What comes forth from the truth and wisdom of his work is “a holy, marveling delight in God; which is Love.” His writing will multiply what you imagine, notice, and behold in the world around you. Julian of Norwich would be proud. You will find yourself ever rejoicing in God.