I am not a paintbrush

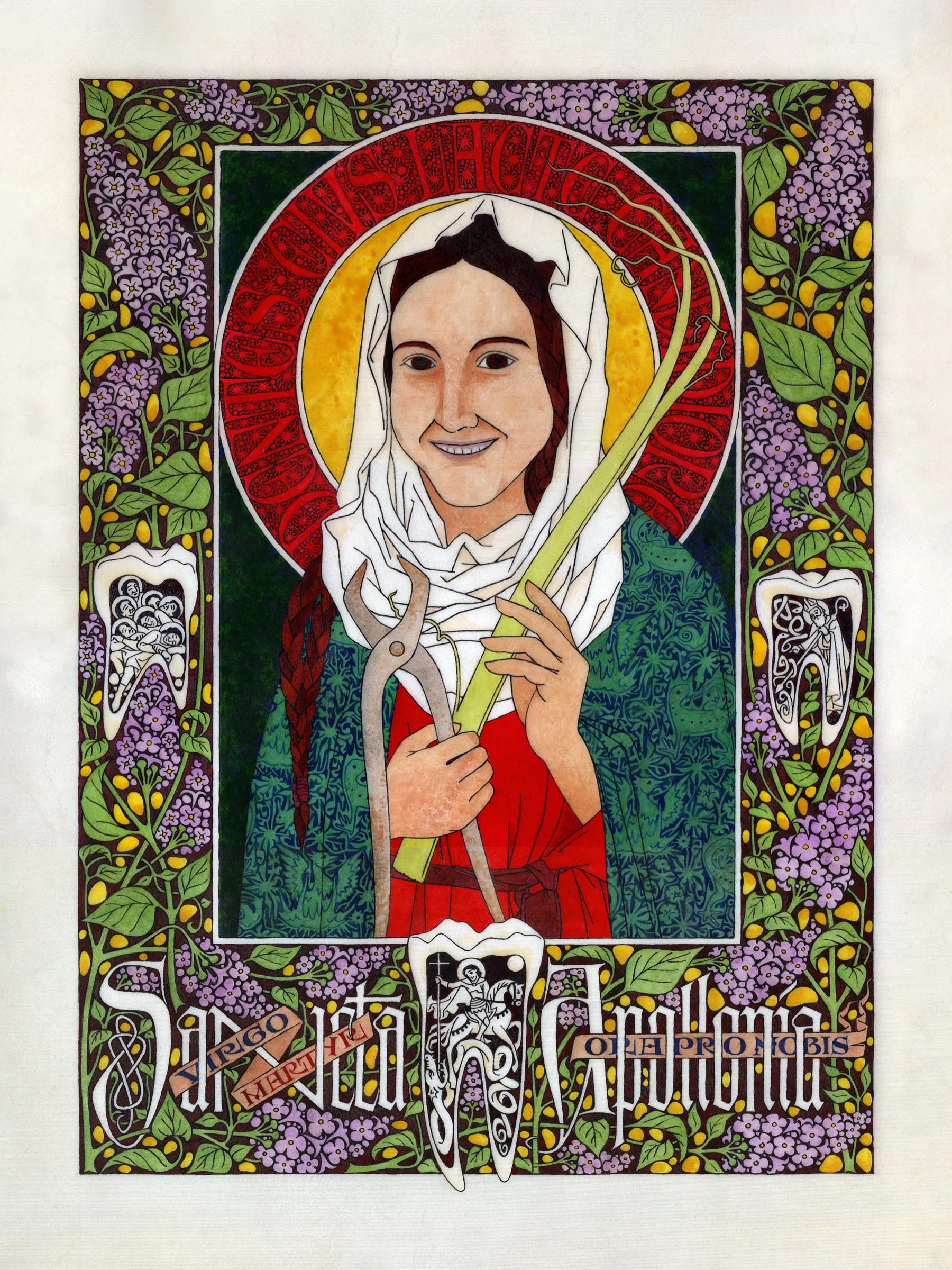

Last year, a Catholic dentist wrote to ask me for a drawing of Saint Apollonia, the patron of dentistry. After a few exchanges of e-mails, we settled on its size, materials, and cost. He had a few specific requests: the saint was to bear a passing resemblance to his niece, and the borders were to include lilac and gold, the colors for dental surgery in academic heraldry.

This past May, I drew the picture in ink on a sheet of goatskin parchment. I followed the instructions, but made my own decisions for the style, composition, ornament, and lettering. It was my choice to depart from the usual conventions of Gothic illumination and depict the saint with her teeth visible. I added a few details entirely my own; my favorite is a cross section of a molar in the bas-de-page, containing in its cavity St. George battling the mythical tooth-worm.

In an agreement like the one I had with this dentist, the person who receives an initial set of instructions and then brings a completed image into existence is called an “artist.” The person who gives the initial set of instructions is called a “patron,” and is expected to pay the artist. This is how things have always been done where professional art is concerned. (In free societies, that is. There have, of course, been situations where artists have been enslaved or otherwise coerced into working for free.)

The people who type prompts into programs like DALL-E or Midjourney or Stable Diffusion, and who call themselves “AI artists,” like to argue that they are real artists, and that generative AI is just a tool for them, like a paintbrush. But in that analogy, the dentist who approached me about the St. Apollonia project was the real artist, and I was a tool, like a paintbrush. No ordinary person has ever used the terms “artist” or “tool” to mean what the prompt-typers are trying to make them mean now.

In order to call themselves artists, the “AI artists” need to adopt a definition of art so expansive that it includes any activity involving human decision-making, including typing prompts. Such a definition would make literally everyone an artist, and therefore be practically useless. If it makes the prompt-typers feel good to call themselves artists, I suppose I can’t take that away from them—our society generally lets people identify themselves however they want. But the modicum of art (in their definition) contained in such algorithmically generated images is no more than what is contained in the typed-out prompts on their own. (Arguably, there is less; the typed-out prompts on their own would presumably be displayed in a typeface that a person thoughtfully designed.)

I find it perplexing when the prompt-typers argue that what they do requires special talent and skill, that using these programs properly is a task that most people couldn’t do well. I’m sorry, but no it isn’t. The entire premise, the entire promise, of generative AI programs is that anyone can use them successfully. The people who make and market them say as much. If their algorithm-writers ever became convinced that such programs required unusual ability, they would rework them until that was no longer the case. Saying that using Midjourney is hard work for you is like telling the world that you find making boxed macaroni and cheese difficult. That admission makes your claim to be a chef less convincing, not more so.

And yes, according to the broadest of the definitions in my dictionary, a chef is “someone who prepares food”. So someone who prepares a box of Kraft Dinner on the tenth try is (in that sense) a chef. In ordinary parlance, however, a chef is someone who can make food from scratch, and invent his or her own recipes. A self-proclaimed chef who can do neither is regarded as either deluded or dishonest.

Saint Apollonia by Daniel Mitsui

It is a peculiar habit of modernity to think that the only things objectively real are those that can be quantified. This habit probably started in those centuries when philosophers and scientists regarded a world of Cartesian grids and physicists’ formulas and aggregates of fundamental particles as primary reality. But it has fixed itself in the thought of everyday people, even after the philosophers and scientists have moved on from that worldview.

This habit affects all discourse about art. It is endlessly repeated as a truism that “art is subjective”. In my experience, anyone who denies this will be challenged to rank works of art, to declare which is better within a few seconds. If he or she cannot, this is considered a decisive defeat. But saying that art has objective principles and saying that art can be plotted along a single linear axis representing its merit are entirely different things. Any artist who seeks to do something with excellence will quickly realize that more than personal taste is at work.

The essence of a thing cannot be reduced to a number; at most, numbers can describe certain of its attributes. Art, like many of the most important things of the real world, is recalcitrant to numerical description. So are mercy and justice, truth and beauty, faith and hope. Modern thinkers say and do incredibly silly things when they attempt to quantify them anyway, or—when this proves impossible—assert that they aren’t actually real.

This habit is encouraged by the use of computers: machines that, fundamentally, can only consider numbers. Literally everything processed through a computer must be reduced to a string of ones and zeroes. Thought patterns tend to be affected by the tools people use. “To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” As Neil Postman observed, to a man with a computer, everything looks like data.

That unquantifiable concepts like love can be communicated through a computer at all is due only to the involvement of human will and intellect, and in proportion to it. In some cases, as when a man writes a romantic e-mail to his wife, there is quite a lot of that. But when a Large Language Model is given the prompt “love,” it makes no attempt to know what that truly means; it merely weighs probabilities that associate it with certain arrangements of characters in its dataset.

What is particularly troubling about terms like “virtual reality” and “artificial intelligence” is the implication that a computer can make something that deserves to be treated like actual reality, or actual intelligence, simply by drawing on a large enough dataset, and by having an elaborate enough algorithm to interpret it in a way that is convincing to human sense perception. In other words, the implication that sufficient quantity can make up for a qualitative difference. This notion would have been abhorrent to a thinker like Thomas Aquinas; he regarded intellect as an immaterial power of the human soul, and defined intelligence as the act of that power. Intellect, precisely because of its immateriality, can reach beyond the accidental properties of things to grasp their universal forms.

There are now many people who profess belief in traditional religions and philosophies, yet do not understand these distinctions, or reject them altogether. Some are even using DALL-E and Midjourney and Stable Diffusion to make what they call “AI sacred art”. At present, such images mostly inhabit the covers of church bulletins, and the Internet. I am not aware of them being displayed in actual sanctuaries. But where AI is concerned, everything moves quickly; each day seems to bring news that a line that seemed uncrossable has been crossed. I would not surprise me if much of what I have written in this essay will be out of date by the time it is published.

The encroachment of generative AI into the realm of traditional sacred art is particularly scandalous because traditional sacred art is meant not only to represent the real world of substantial things, but also to connect that real world to a higher spiritual reality. As I wrote in eight years ago in Dappled Things (Why You’re Wrong About Medieval Art), the perspective that sacred art adopts is that of the prelapsarian Adam, or that of the assumed Virgin Mary. It attempts to show how the world looks when seen from the aspect of Heaven.

Hildegard of Bingen wrote something beautiful and profound concerning music, which I think can apply to all art. She said that humans carry within themselves a dim memory of Eden. The reason that a melody appeals to us is that it is like a distant echo of the voice of Adam before the Fall. I think all art, whether musical or visual, is connected to our nostalgia for Paradise. Art, and sacred art especially, make people better by drawing them closer to that beatitude. Ultimately, art comes from something higher than us, something that our fallen selves cannot fully comprehend. No computer program bears within itself the half-remembered dreams of Paradise, and therefore no computer program can comprehend the true source of art, even a little.

“AI art” attempts to build a bridge between a virtual world of pure quantity and the world of human sense perception, not between the latter and the higher reality of beatitude. The question it “asks” of its art is not: “Is this true, good and beautiful?” but rather: “Is this what the person typing the prompt probably wants as an answer?” This represents an ontological shift downward, away from God. At its very best, it attains a level just shy of where real art begins.

The artists on whose work the most popular generative AI programs are trained are not compensated, attributed, or even asked their consent. This amounts to a diffuse theft of intellectual and creative property, even if it is not presently illegal. I think that many people who are not directly affected by intellectual property law assume that it is simple and fair, and that the legal definition of theft more or less matches its moral definition. This is not actually so.

For example, in the United States, typefaces cannot be copyrighted. As a typeface designer, I know from experience that they are extremely difficult and time-consuming works of art to produce. If someone were to borrow a book set in one of my typefaces, scan its glyphs and trace them into a font editor, and sell the result as his or her own work—that would actually be legal. Generally, people do not do this, because anyone who does is denounced as a plagiarist and ostracized by other type designers.

As recently as the 1990s, American art museums were arguing in court that they could regard photographs and scans of the paintings in their collections as their own intellectual property. The ruling in Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., following the logic of the Supreme Court decision Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service Co., established that they could not, as such photographs and scans amount to nothing more than “slavish copies.” Were these cases decided differently, I would be living in a country where any photographer could take a picture of one of my drawings, and then sell prints of that photograph as his or her original work without attribution, or license that photograph for use on t-shirts, keychains, or cereal boxes without my permission.

However, the standard for originality required by the American courts is extremely low, indeed minimal—so much so that a photographer can, in fact, do what I just described, so long as he or she starts by taking a picture of a sculpture rather than a two-dimensional work of art. The mere choice of camera angle is considered enough to establish the photograph as an original work, legally. Generally, photographers do not treat sculptors this badly, but this again is due only to the fact that they would be widely regarded as having ripped someone off. This precedent gives me little confidence that the courts will come to the rescue of artists in controversies over generative AI.

Here, also, the news moves so quickly that I might be proven wrong by the time these words are published. But regardless of what the courts decide, the moral difference between homage and plagiarism is not determined by the law. It is rather a question of how methodically the derivative work copies the original, how much new labor and ingenuity was needed to produce it, whether the original artist was asked permission, and whether the original artist was attributed and compensated fairly. In the case of “AI art,” the answers are: possibly very much, practically none, not at all, and not at all.

There is an even easier way to tell that a theft has occurred: whenever someone is getting something for nothing, or for less than its real value, someone else is paying the price. If that someone else did not agree to pay the price willingly, he or she is being cheated. It is obvious that the artists whose work is scraped from the Internet to train AI programs are contributing something indispensable, and that they are receiving nothing in return for it.

Other artists of the past have seen their worlds changed by new technology. The invention of movable metal type, for example, certainly affected the art of manuscript illumination. (Although the result was not nearly as destructive as one might suppose; calligraphy remains a vital art form to this day, more than five centuries since the Gutenberg press arrived.) But the Gutenberg press did not need to pilfer directly the existing work of scribes and illuminators in order to operate. It rather demanded its own artists and craftsmen—type designers, punchcutters, carvers of metalcut or woodcut pictures, pressmen—who developed their own skills through study and practice. And while these new kinds of artists began by imitating the conventions of manuscript illumination, they soon learned that their medium had its own distinct limitations and possibilities.

AI programs are not comparable to this. By eliminating every artistic process except that of prompt-typing, they remain dependent on other people’s work. It is difficult to think of a historical comparison for the role the prompt-typer takes here: perhaps that of an ancient overseer commanding slaves to build a ziggurat, if the slaves also happened to be the architects. Or a sweatshop foreman paying seamstresses a pittance to sew designer clothes, if the seamstresses also happened to be the fashion designers, and the pittance were done away with altogether.

These programs will, of course, drive real artists out of work. I am not worried for myself, because I work directly for patrons who specifically seek me out, and because the sort of people who commission the religious drawings that are my specialty tend to value authenticity. But many artists depend on commercial projects to make a living, and many work for corporations. Even those corporations that ostensibly exist for an artistic purpose (like movie studios or book publishers) usually have as their ultimate priority not artistic excellence, but the maximization of profit. AI threatens to replace any artist whose boss would be willing to accept a result that is (in the boss’s mind) half as good, if it could be gotten for 49% of the cost.

This is why I do not expect the market on its own ever to decide in favor of good or real art; artistic excellence has never made sense as a return on investment. The best artists are those who are willing to spend significant time and effort to improve their work in ways that most people will never even notice. This is true even of those whose work is widely popular; it is always better than it needs to be to make the money that it does. All good art comes into being on the far side of a diminishing return.

Some might question whether the loss of work among commercial artists, or in the entertainment industry, is all that important. “Who cares what advertisements look like?” they might ask, or: “It’s just a popcorn movie; why does it matter how it was made?” I ask them to consider that these are the kinds of art that reach the most people, that surround us most completely. Almost everyone spends more time looking at advertisements and mass entertainment than fine art, even if he or she prefers the latter. These are the works of art that many children encounter first, and those have a formative influence on their imagination and aesthetic sense. Nothing good can come of having the things that pervade our lives stripped of their humanity, thoughtfulness, and craft.

While fine artists may not be threatened with outright replacement in the way that commercial artists are, they are nonetheless harmed by the proliferation of “AI art.” One obvious way is that it has made the Internet far less useful as a means for independent artists to make their work known to the world. Search engines and social media feeds are now overwhelmed with algorithmically-produced images and bot-written articles. This actually hurts all small businesses.

I started my professional career around 2005, with a website and a blog. In those days, it was possible to get thousands of people to engage with them every day, just by publishing interesting content. That was how I found my early patrons and customers, who commissioned enough drawings and bought enough prints that I was able to become a full-time professional in 2010. Back then, I would reliably see a surge in print sales whenever a group of people online discovered my work for the first time, as when it was featured in an article or on a popular website.

In the years since, more and more time has been required to get attention online, with fewer and fewer results. The fact that I can continue to make a living is due almost entirely to commissions for original drawings, which I probably would not receive if I did not have an already-established reputation. I cannot imagine how difficult it would be for an artist to start an independent career now. How would he or she ever find enough patronage when the Internet is barely useful for this anymore?

AI will lead to the actual art becoming more predictable and mediocre, as artists of the next generation are taught to accept it as normal, and encouraged to use it as an aid to their own creative process. Inevitably, this will create in some of them a habit of imitating the algorithmic results, the consensus of the dataset, by default.

The algorithmic results may improve somewhat over time, because “AI artists” are training the programs just by using them. The more the prompt-typers reject images that have the wrong number of fingers, the fewer such images the programs will generate. However, another problem is likely to arise, that of feedback. As the Big Tech companies continue to gather images from the Internet, they will encounter more and more that were made using programs like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion. The “AI art” will be trained to imitate other “AI art.” As the datasets become more inbred, so to speak, whatever flaws and biases are present in the algorithms will become apparent in ever more obvious ways, like genetic diseases emerging in a family after several generations of cousin-marriage.

Generative AI is entirely controlled by the large corporations that have the means to collect so much data in the first place. Every place that it is applied, it increases the mastery that Big Tech exerts over the lives of ordinary people. Those who assert that it is a tool, like a paintbrush, need to imagine a world in which only a few Big Tech companies produce paintbrushes, and can make decisions that determine what sort of paintings they produce, and change those decisions whenever they want, without any transparency.

Some of the problems I have mentioned are ones that, theoretically, could be fixed, although I see no indication that anyone is seriously trying to fix them. But even in the best imaginable future for this technology, “AI art” generators would still be nothing more than diverting simulations—video games that let their players pretend to be artists. They would be to art what MLB: The Show is to baseball: something that no reasonable person would ever mistake for the real thing, done at any level of skill.

Personally, I am terrible at baseball, but I still like it and play it in the back yard with my kids. And I know how to make macaroni and cheese from scratch. And I will continue to draw and paint and calligraph and design typefaces and write poetry for as long as my mind, body, and financial circumstances allow me to do so, without using AI programs as any part of the creative process. I believe that it would be wrong for me to do otherwise.

A lot of contemporary discourse about art treats its pursuit as a matter of “following your dreams” or “doing what you love.” And while this is not always incorrect, it misses something important. Art does not fundamentally exist for the purpose of making the people who make it happy. If making art were a reliable way to be made happy, then the most prolific artists in the world would be the happiest people—and they manifestly are not.

Seriously good artists, in my observation, are motivated less by a desire to follow their dreams than by a sense of duty to use their abilities to make the world a better place. They care deeply about the traditions they hold up and hand down, about the effect their art has on the people who encounter it, about the ways it will influence artists of later generations. This concern for the past, present, and future affects their decision-making at every stage of the creative process. They are willing to sacrifice a great amount of their personal comfort and contentment, and even more of their time, to make their art as good as it can be—less for their own sake than for everyone else’s.

When real artists complain about “AI art” and its promise to replace their years of practice, study, observation, and self-criticism with a quick, effortless, and automatic process, they aren’t mad because they might seem less special, or resentful because they might lose an opportunity to make money doing what they love. Such feelings wouldn’t elicit much sympathy—a lot of people don’t get to make money doing what they love.

Real artists are, rather, concerned for art itself, which is one of the few things that has reliably brought meaning, truth, beauty, and goodness to people living amid pointlessness, falseness, ugliness, and wickedness. Art is one of the best ways by which people, even those without wealth or power or prestige, can say things that are received by many, and that endure. It can communicate the most important things in life, across centuries and continents, across cultural and linguistic and religious boundaries. It can open other people to joy, fellowship, love, humor, romance, adventure, divine revelation, comfort in times of tragedy, hope in times of despair.

None of these things is quantifiable; none of them can be reduced to binary code; none of them can be understood or meaningfully communicated by an intellect that is less than God-given. Art does not need to be redefined or replaced. It is not a problem to be solved. To accept something generated by AI as art requires the redefinition of art. The replacement offered is immeasurably and ontologically inferior.