Hildegaard and the female voice

Once upon a time, in the ancient mists of my twenties, I began a love affair with the Medieval world. I was sent a saint to woo me to its heart. Introductions were made by a friend who, for her own part, in no way wished to be woo’d by the Medieval world. She was a feminist. But she was also a friend. As the quirky mystery of providence would have it, she was given two tickets to a concert at the Cathedral downtown and she asked if I wanted to come with her. I’d like it, she said. It was all songs by a Medieval woman. I was intrigued.

Upon arrival, we found ourselves in a darkened Cathedral whose sanctuary glowed with candles surrounding one very small chair. The Cathedral is cavernous - a great cave of height and breadth; daunting to those who enter the large heavy doors and catch a first glimpse of it. You feel instantly small and yet strangely not insignificant. Vast as it is, you realize you belong there - as though you have been invited to find your greater self - to be worthy of such a space.

But to perform there? That is a different story. There was to be one singer. A woman. And as the audience slowly ceased their murmurings, out she walked, very small indeed. I instinctively wanted to sit next to her, so she would not feel so alone in the dark cave that surrounded her, tucked away as she was in a pathetically small bower of candlelight. She paused for the space of a presentiment and then began to sing. I knew then that I need not have worried. She was not alone. She was singing to a lover. I felt Him catch her song in His hands, this Beloved, and release it like birds to our own waiting hearts. It was only one voice. Clear. High. Strong and resonant. Filling up an impossible space with an unbridled joy feathered with filigreed song. It was, I discovered, the song of Hildegard.

Hildegard was a German Abbess in the High Middle Ages. She joined the monastery as a young girl and lived and loved there all her life. She was a marvel. She was a poet, she studied medicine and medicinal herbs, she delved into philosophy and theology with such intelligence and insight that she received the illustrious title: The Sybil of the Reine. She was filled with exuberance and inquiry. The whole world was a window into the Divine for her. She loved and she loved with her whole body as well as her soul. And never, she was to discover, were the two so joined as when they were singing as one. Hildegard wrote hymn after hymn after hymn in praise of this unity offered like incense to the Beloved Bridegroom, Christ.

She wrote her music not just for any soul and body. She wrote her music for women. For her nuns. A whole house full of them. It is said that when she was Abbess, she wrote a secret language that only the nuns in the house knew - Lingua Ignota. This was the language of their songs and hymns; it is how they communicated with each other, how they expressed their joy-filled unity in the mysteries of God; a God who had created them each with a woman’s unique view of His world - the feminine genius - and had gathered them together to voice its truth. Hildegard was sent for the express purpose of teaching them how. In a world dominated by the voices of monks, rich and low and beautiful in their own right, Hildegard was to add that feminine descant which flew and floated above their steady song like a chaste and fragile bird - completing and complimenting the offering.

It was the joy of the thing that moved me that night. The evident joy of this one woman using only the voice God gave her to carry her praise out and up to Him. I felt myself crying in the dark, not from sadness, but from a joy that needed tears to express it. As Oscar Wilde said so correctly, “Some things are so beautiful, only tears will do”. I never forgot that first taste of Hildegard. She ushered me into the wonder of other Medieval music. But none was to be as lilting, mysterious, or sensually holy as hers for me.

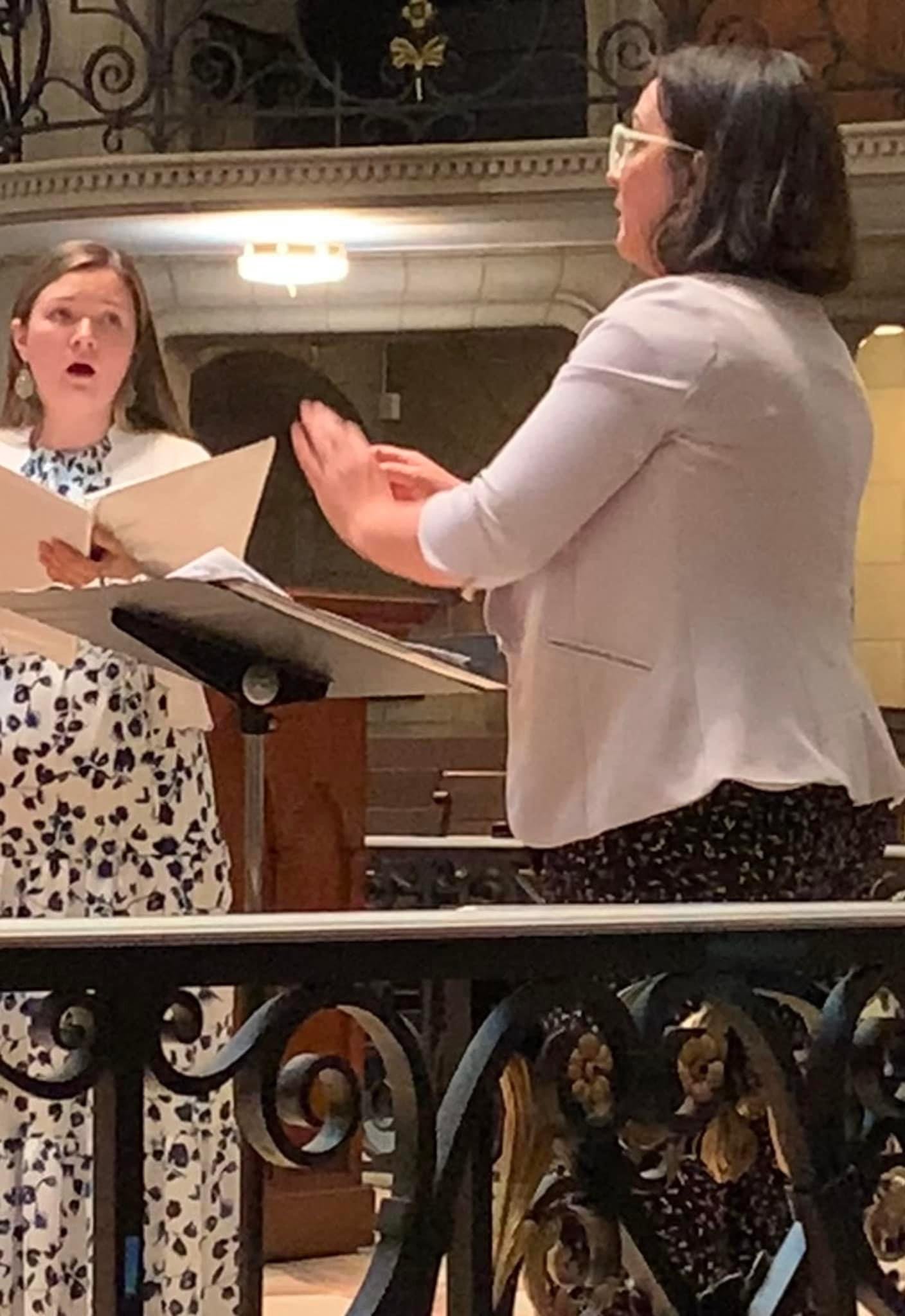

Fast forward from these mists of time to the present state of things. I am older now. I still love the Medievals with the greatest part of my heart, but for many years I hadn’t really thought of Hildegard, somehow. As it happened, I was invited to another concert at another Church. And to my surprise Hildegard was there and being sung - by women. I spent the next hour and a half saturated with joy both by the music and from gazing at the faces of those who sang the beauty into existence. These women, as one harmonizing voice, gave themselves over to the woven magic of Hildegard. It was palpable, that joy.

As it turns out, they form a choir that is aptly named Polyhymnia - the Greek Muse for the highest and best poetry and song. They were true to their name. At the head of this lovely cadre of singers was one Nori Fahrig. Her name alone had a romance about it. I always regretted not being able to ask Hildegard any of my burning questions about the mystery of song and the feminine power of women who sing it, but here was this little woman with the quirky, lovely name directing music that reduced me to tears - a woman who knew Hildegard’s muse, and intimately. I wanted to find out what made her tick. What compelled her to direct music, and women most of all. Where was God in her work? How did she stumble upon this unique vocation?

Well, I did ask her, being quite nervy that way. And she, of the lovely name, graciously consented to answer my questions. I had no inkling of the story that was about to unfold. In her own words, Nori wove a tale of providence just as miraculous as Hildegard’s which left me speechless. It gave me a strong conviction that art is a solemn gift given to whom God wills and that so often it is reached by suffering and perseverance. And that God will not be outdone in generosity to those who are faithful to that journey.

So, I simply asked questions. Nori told the story.

Was music always an important part of your life?

Music was innately important to me. When I was one year old, my mother bought me a little toy piano. There is a picture of me with my hands perfectly posed on the keys. I remember seeing a real piano when I was about four or five at my uncle’s home. Sadly, this was around the time my mother had left my abusive father, who was still allowed to see his children. My uncle’s house was the rendevous point.

I was instantly drawn to this instrument somehow when we entered the house; to the polished keys and the sounds they made. My mother was picking up my brother who was visiting my father there, and she brought me along. And, as usual, my mother and father began to argue loudly. To distract my mind and hopefully theirs, I decided to plunk out some tones thinking, in my simple four year old logic, that I could calm their rage by playing. Somehow I knew that was what music was for. To calm. To bring peace. I tried my best.

Strangely, my mother was not at all musical, but somehow she found it important to make music available to me. I listened to the usual pop music of her generation. But she also owned a few random classical records like The Nutcracker. I took ballet for about five years, and the Nutcracker had become the soundtrack of that happy time in the studio.

Once in a great while, my mother felt oddly moved to take us to vespers at Saint Mark's Cathedral in Seattle, Washington where I grew up. I have vague memories of darkness illumined by candlelight, filled with the sound of chanting. It was very mysterious. It captured my imagination.

Did you formally study music?

I had been obsessed with the piano since I saw my uncle’s old, parlor, upright grand that day. I knew I had to learn. At the time, my mother had taken a job as a janitor at my private Lutheran grade school. This made it possible for us to attend. Every day we would be accompanied on the piano, singing the Lutheran hymns. I was captivated watching the teachers' hands.

I wanted to learn how to play the piano so badly, but domestic violence and poverty in my home did not allow it to happen until I reached the age of thirteen. My mother told me later that she found an urgency to do it then since I was getting too old and it was now or never. Even then we couldn’t really afford it, and it would have enraged my new step father who was violent and drug addicted. My mother managed to hide the piano lessons from him.

My teacher was a young pianist who taught at the local Lutheran College down the street. Listening to the Classical radio station gave me a few piano pieces to be obsessed about. Moonlight Sonata by Beethoven, Prelude in C sharp minor by Rachmoninoff, Schuman’s Piano Concerto in A minor, and the Minute Waltz by Chopin.

I did not have a piano at home so I practiced after the lessons in a practice room at the University. Unfortunately, these lessons only lasted about six months. My step father found out and put an end to them.

I did not give up. I went to the local Lutheran church and begged to be allowed to use their pianos for practice after school. They kindly obliged me and I was able to plug along teaching myself for the next year or so.

My mother had since gone to nursing school, eventually left my step father, and was working at a hospital. The lessons resumed. At the age of sixteen, I met my first, real piano teacher, who had traveled from Moscow to Seattle to get her Doctorate at the University of Washington. She, too, had fled her husband and brought her toddler son with her. She was the strongest person I had ever met, and she supported my desire to travel to the East Coast to pursue music. She wanted me to go to Julliard but I was told that I started my piano studies far too late and that I was competing against legacy students from high end prep schools. I did not despair.

I was eventually accepted into a few different East Coast conservatories but was given little to no scholarship money. My poor mother’s nursing career had come to a halt due to closures and cuts. She was in debt and had not paid the bills or the mortgage for some time. We sold all our worldly goods to make ends meet, and moved into my grandmother’s one bedroom apartment. A week later, my mom announced with conviction that she was going to send me to Boston with the high hope that the conservatory there would just work something out for me if I showed up on their doorstep. She even sold her refrigerator to buy my plane ticket. Armed with that kind of support, I went. And of course they had no intention of working anything out for me. In fact, I was laughed out of the financial aid office when I suggested going part time at least. But there I was, signed up and living in the dorm. Not for long.

Late one night, they told me I had to vacate the dorm and leave campus. I wandered homeless on the streets of Boston for a couple of weeks. I would crash at the local youth hostel in their common area or I would stay at a kindly church woman’s house until she got sick of her own charity and the inconvenience it brought (she was a Unitarian after all!) In the end, I managed to get a room and a job as an apprentice to a local piano shop that serviced Berklee College of Music. I learned to tune and rebuild piano actions.

Shortly after landing the piano shop job, I met a local Catholic priest. There was a Eucharistic Shrine near my former conservatory. I would go sit in the quiet of the church to pray before I would sneak into the conservatory to practice the piano late at night. Eventually the piano shop let me practice there, but I had to do it very early: at 5:00 AM before the shop opened.

My new priest friend happened to notice my piano books and offered me a ‘little job’ playing at a small chapel they had in the local mall. I ended up doing that ‘little job’ for over ten years. It started me on my conversion to the Catholic faith. I had grown up Lutheran and later did a lot of Mega Church hopping. I had, at last, found my home in the Catholic Church.

Eventually after years of hard work at many different jobs, I got myself to the point of financial independence, and I had achieved some hard won emotional healing from my childhood. I felt it was time to finally get that elusive degree. I ended up with both an undergraduate and masters degree in piano performance from the Longy School of Music at Bard College. This was a little music conservatory tucked next to Harvard Square in Cambridge. I learned many wonderful techniques at this school. I had my degree. I had arrived.

How did you make the journey into choral music?

I have fond memories of Junior High and High School choir. When I was a sophomore in high school my choral teacher was a doctor of music and had an attitude as long as his degree. In short, he was a jerk. He did a lot of yelling and was obviously not thrilled at having to teach high school students for a living. But he did come with very high standards and managed to teach us a choral fugue setting from the Magnificat by J.S. Bach. That was the magic moment for me; the first choral piece that had really gotten to me deep down. Musically and mentally it was everything to me. We ended up going to state with that piece. That was the beginning of my passion.

Having a church choir job, I, by necessity, started directing volunteer choirs. When at the conservatory I took an orchestral conducting class, but the specific methods of ear training and rhythmic training I received through my college degree helped more. Combining my experience singing soprano for good conductors in a variety of choirs, singing for multi-denominations in the Boston area, and my time as an assistant conductor for the Parish Choir at Saint Pauls in Harvard Square, where we seriously performed Gregorian Chant, all these experiences contributed to building the foundation for my deep and lasting fondness for choral music even to this day.

Singing is the most intimate form of worship. It forces us to leave our egos and masks behind to expose our flaws, and tepidity. Singing requires both physical and mental effort and it is something we give. Of course, we get satisfaction from it but I find it forces a sort of human humility.

How did Polyhymnia come about? What is it about these particular women that makes the sound so unique? Are they all professional singers? Amateurs?

Polyhymnia came to me as an idea shortly after moving from Boston to Saint Louis. My husband and I moved the summer before the infamous Covid year, 2020. I had been taking a variety of music gigs since I was new to the area and the demand for experienced singers and organists in Saint Louis is high. During my adventures I experienced the sound of many good female voices that I could tell were skilled but not being used to their full potential in male dominated choirs.

One pivotal evening during Mass, myself and another lady were essentially relegated as background singers for the men. We sat there, the two of us, barely using our voices while the men sang all the major chants of the Mass. At one point, the director told me to sing “lighter and quieter”. My inner annoyance at this request was anything but lighter and quieter. I made two vows that evening. One: never to waste my time with that particular director again, and Two: I needed to start a women’s choir.

Right before the pandemic hit I had contacted the ladies I wanted in the choir and had asked if they would be interested. To my utter surprise, they were enthusiastic. Many of the ladies have college or conservatory degrees in music. Those who do not have degrees specifically in music, have acquired advanced choral training from high level choirs in places like the St Louis Cathedral and Saint Francis de Sales in St. Louis. Some are music directors themselves for parishes in the area, some have specialized in solo vocal repertoire. We have one choral scholar who is in my program at Saint Joseph’s Church. She is a teenager who is a sort of apprentice to the group. She is training in the Bayer Fund Artists-in-Training Program with the Opera Theater of St. Louis. Each from here and there, they all became friends.

I believe their sound is unique in the fact that they are all practicing Catholics. I have always held to the truth that believers are more believable when they sing the faith. In Boston I had a bounty of professional singers working for me. I had my pick of the many music conservatories in the area. My church was known as one of the few that regularly performed Gregorian chant. So, I attracted the local Ancient Music Department's interest. I had wonderful cantors that would perform Hildegard and the Gregorian chants with an ease and flexibility that was astoundingly beautiful. One of my last years in Boston when I was the acting assistant organist at Saint Paul’s Choir school in Harvard Square we had one of our professional men sing the Exsultet, a prayer of deep faith and exultation. It cannot be faked. This man cared more about the beauty of his tone than the words he sang, and although beautiful technically, my heart was saddened. There was no joy of belief. And this was the heralding hymn of Easter calling us out of darkness into the light of the newly Resurrected Christ! Sacred Music needs voices who believe. Even a common, untrained ear with faith can hear the difference. It happens on the metaphysical level of spiritual awareness. It’s an energy that is felt in the senses. When we have that spiritual energy it is tangible in our flesh. There is an electricity I feel in my body when I sing sacred music. It’s a sort of charge that to me represents truth/presences/reality, and I think a very real revelation of the spiritual meeting the earthly. I find this revelation each time I sing with the women in my choir.

The simple human voice is representative of our incarnated selves and is not a construct of the mind. Nowadays with our online existence do we know the difference? We see a world around us chaotic and imbued with personal realities of the mind and denial of the realities of the flesh. Singing is very tangible and also resonates frequencies in the body that cannot be replicated elsewhere and thus are unique and unrepeatable. As each human is unique, the voice is so unique to each performer. There will be imitations, perhaps, but those unique voices will never be repeated on this earth. I suppose there is something pro-life in that outlook. We literally won't hear the physical voice of Jesus until the end of time, when we are at last with him. I for one am looking forward with great longing to one day hearing and knowing that unique voice - the voice of my Incarnated Lord. Perhaps He will be singing.

I left this interview with Nori overwhelmed and humbled. Her long and faithful journey of faith, her overcoming of a sad and hurtful past, her joy in music, her championing of the unique mystery found in women’s voices. I am honored to know her. I am blessed beyond measure to have seen and heard her in action - to witness the passion of her heart and the Divine electricity passing from her voice to the voices of her choir to make a joyful noise for the Lord. And, I ask you, what better gift can we give one another on this journey to the Father than joy? How can we keep from singing?

St. Hildegard, pray for us.