Europe in these times

Elche, Spain, 20 March 2025

A striking Pietà—a sculpture of the Blessed Mother cradling the dead body of Jesus after His crucifixion—greets the visitor to the Mystery Man exhibit, setting the tone for an experience designed to help one understand, and gain understanding from, the Shroud of Turin. Michelangelo’s Pietà is of course the most famous in existence, and it established characteristics that were replicated in hundreds of subsequent sculptures of the same scene over the centuries (namely that Mary appears younger than Jesus, her face sorrowful but serene). In contrast, the Mary that greets visitors to the Mystery Man exhibit is old, her deeply-lined face twisted skyward in intense agony, her hand pressing on a wound in her son’s side, trying uselessly to stanch the bleeding. Together with an equally unapologetic and brutal ecce homo sculpture (both are the work of Spanish sculptor Ricardo Flecha Barrio), it sets the tone for an exhibit that is, throughout, moving and effective for the very reason that it displays and explains the intense physicality of God made man, of His suffering and death. Haunting and often difficult to behold, the exhibit is an intimate, painful, and beautiful entry into the mysterion at the heart of Christian faith, leaving the visitor no doubt as to the sacramental nature of a world and an existence ennobled by the fact that God became human, suffering as a human in a human body for human salvation.

The Mystery Man exhibit has visited cities in Spain, Italy, and Mexico since opening in 2022, and organizers intend to bring it to five continents (including planned stops in the United States—dates and locations not yet announced) over the coming months and years. Spread out across several rooms, it delves into all of the facts surrounding the Holy Shroud, including the story of when it first appeared to a wide public, its journey to Turin, and the various scientific studies undertaken to confirm or deny its authenticity. But it is the tactile, the physical, that truly sets this exhibit apart, making it highly worth the visiting.

A display case in the room after the Pietà contains thirty actual Roman coins from the first century, actual Roman speartips from the same period, and replica nails of the size and shape thought to have been used for the crucifixions of that time. The type of wood used for the cross, and what was inscribed on that wood, is explored. Perhaps the most important items in this same display case, however, are replicas of the flays that were used to whip Jesus during the Scourging at the Pillar: one-foot long sticks with several leather lashes tipped by small metal balls. Their effect when first seen is little, but becomes profound when one reaches the end of the exhibit. The same can be said of a display case explaining how scientific study supports the belief that in Jesus’ crucifixion (as in any crucifixion), the nails must have been driven through the wrists rather than the hands. The explanation for this assertion is nothing short of brutal, but profoundly important for and consistent with the overall message of the Mystery Man. That is, the entire experience leads to an explanation, and then a visual display, of what the Shroud—if taken as real—tells us about what happened to Jesus, and what His body looked like at His crucifixion and death.

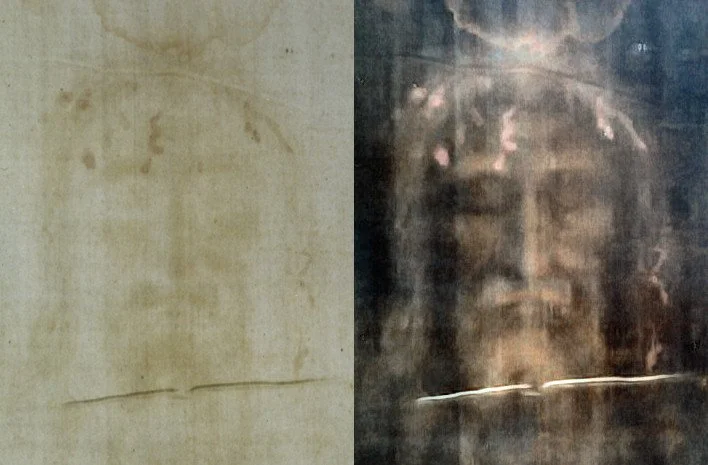

There is an exhaustive description of the Shroud in the penultimate section of the exhibit, delving into the various stains on the cloth, and what they tell us about the wounds Christ suffered during His Passion and death. Fluid stains indicate where flays whipped His flesh, where His forehead was pierced by thorns, where His side was stabbed by a spear, the way in which His knees were gashed from falling repeatedly. A longstanding controversy about the Shroud is also put to rest in this section: the fact that only four fingers of each hand made a mark on the cloth was long interpreted as evidence that it was fraudulent, but subsequent scientific study showed that any human hung by nails through the wrists would experience the phenomenon of his thumbs folding under his palms. Even the most basic of findings revealed in this portion of the Mystery Man proves moving for its sacramentality: according to the stains on the cloth, Jesus had an AB blood type.

All of the displays and information, of course, build up to what will be seen in the last room of the exhibit: under a replica of the Shroud of Turin, a life-size re-creation of the Body of Christ as the cloth indicates it would have appeared when wrapped for burial. The sculpture is incredibly realistic, down to the small hairs on the arms and legs, but it is the graphic and extensive wounds that leave one stunned and speechless. They number in the hundreds, leaving almost no parts of the body unmarked. The suffering they indicate would have been unbearable—a fact made all the more shocking given the knowledge that they were inflicted over the course of hours. That this human body suffered in this way is of course basic Christian knowledge—but the sight of it so realistically and faithfully presented is something that no observer will ever be able to forget.

This, of course, is the very point of the Mystery Man: to draw one into the physical reality—the sacramentality—at the very center of Christian belief. That one might have touched the coins and measured their weight in the sack, or been pierced by the nails and spears, rubbed flesh against rough wood, gashed knees on the ground, felt the flaying of the whips. That one might have sweat and bled. That one might have lived a human life with human suffering. That one would have loved his mother. That she would have wept and wailed while cradling him come down from the cross, trying to stanch the flow of blood from His dead body because she loved her baby become a boy become a man become the salvation of the world. That she would have loved God.