Friday Links

Breaking Down the Walls of Time

The World Beneath the Couch Cushions

TS Eliot’s 20th-century nightmare

This 1,200-Page Poetry Book Affirms Seamus Heaney’s Towering Genius

The Translated Word

A Thrill of Hope: The Weary World Rejoices with Shemaiah Gonzalez

Breaking Down the Walls of Time

Read the whole interview. You won’t regret it:

One of the great rewards for a writer is to sense oneself breaking bread with the dead. The act of writing is in that very private or subjective sense a way in which the walls of time break down, and we discourse among ourselves in eternity. It’s such a blessing to be able to participate in that conversation though the humble act of writing a single line of verse.

The World Beneath the Couch Cushions

Some more of the delightful Nadya Williams. This time on “The World Beneath the Couch Cushions.”

What does it mean to look at the world through the eyes of a child? It means to see the table under which one can still walk without bowing one’s head as a tunnel, a doorway between worlds, an extraordinary castle inside an ordinary house. It means to see that tiny hole dug up with a toy shovel in the yard as a quest for the discovery of dinosaurs on this very property. It means to see the nightly bath as a vast ocean, albeit one quite safe from any danger, and oneself as a mermaid traversing the deep on an adventure that will conclude safely in a fluffy-toweled hug, warm pajamas, and a bedtime book. And it means to see the world hidden within the couch as a kingdom entire—a kingdom worth longing for, whole somehow, miraculously untarnished by the brokenness that adults know too well. It is not only gummy bear vitamins, after all, that get lost in it—yet find a new life in the child’s imagination. The fuzzies that attach themselves to said vitamins and anything else within the couch interior get redeemed in this mysterious world as well, transformed into a mist that must naturally accompany the attendant magic.

TS Eliot’s 20th-century nightmare

The Hollow Men was Eliot’s first major poem after The Waste Land three years earlier – quite the tough act to follow. It begins like a march (“We are the hollow men / We are the stuffed men / Head full of straw”) before plunging us into a purgatorial landscape, broken images appearing like traumatic flashbacks (“sunlight on a broken column”, “a tree swinging”, “a dead man’s hand”). As its five parts progress, we encounter stars “fading” then “dying”, and human expressions and senses declining in power – “quiet and meaningless” whispers lead to “sightless” people who gather on a beach and “avoid speech”.

This 1,200-Page Poetry Book Affirms Seamus Heaney’s Towering Genius

This new collection of his great work, at well over two inches thick, is “great” in a workaday sense of the word, as well. That it might be called a “doorstop” is the kind of homely, conventional joke that would be more likely to amuse, rather than offend, Heaney’s many-minded imagination. His work is magnificent, to use a Yeatsian word, partly in its capacity to see human doings, such as books, in many ways at once.

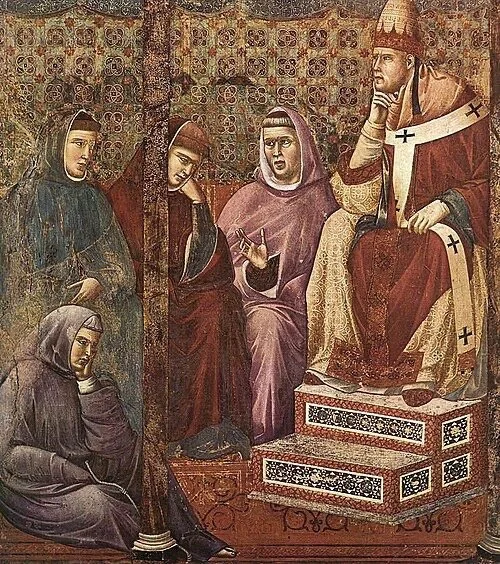

The Translated Word

Bishop Flores on: “What conversion looks like”, or perhaps “a lecture in praise of the Charity of Jerome and Augustine”:

The primordial translation of the Word among us is a move that gives birth to new words in us that have to do with the fact of his presence and the understanding of his person; basically who he is and why he comes. These are words we would not have thought to think and say before. The only reason we are interested in translating words about him, even inspired words, is to perceive what the enfleshed Word among us is saying to us by being who he is, and by acting as he does while he is with us.

You can also listen to the video HERE.

A Thrill of Hope: The Weary World Rejoices with Shemaiah Gonzalez

Shemaiah will be hosting a writing seminar over three biweekly sessions (on Tuesdays). “Each week we will explore literature that speaks to the auspicious longing we hold always, but especially in Advent.” Sounds wonderful!