A Spiritual Atheist’s Gospel Film

My mother-in-law recently introduced my nine-year-old daughter to a bird app. Now when my daughter walks with her tablet through my wife’s garden, the app records every melodious bird call and identifies each bird based on its distinct sound. I’ve enjoyed seeing her excited face each time she tells me the new bird she’s discovered living around our home. And her discoveries have helped me uncover a sense of existence I never realized I should notice. Before, whenever I worked in the yard, played volleyball or baseball with my kids in the yard, helped my wife in her garden, or chucked tennis balls around for my black lab, bird sounds were just noise. I heard them but never attentively listened for them. But now, the bird skronk around my home has transformed into the unique songs of warblers and cardinals and robins and bluejays. A new sense of being now sings through the trees and flowers and sky around my home.

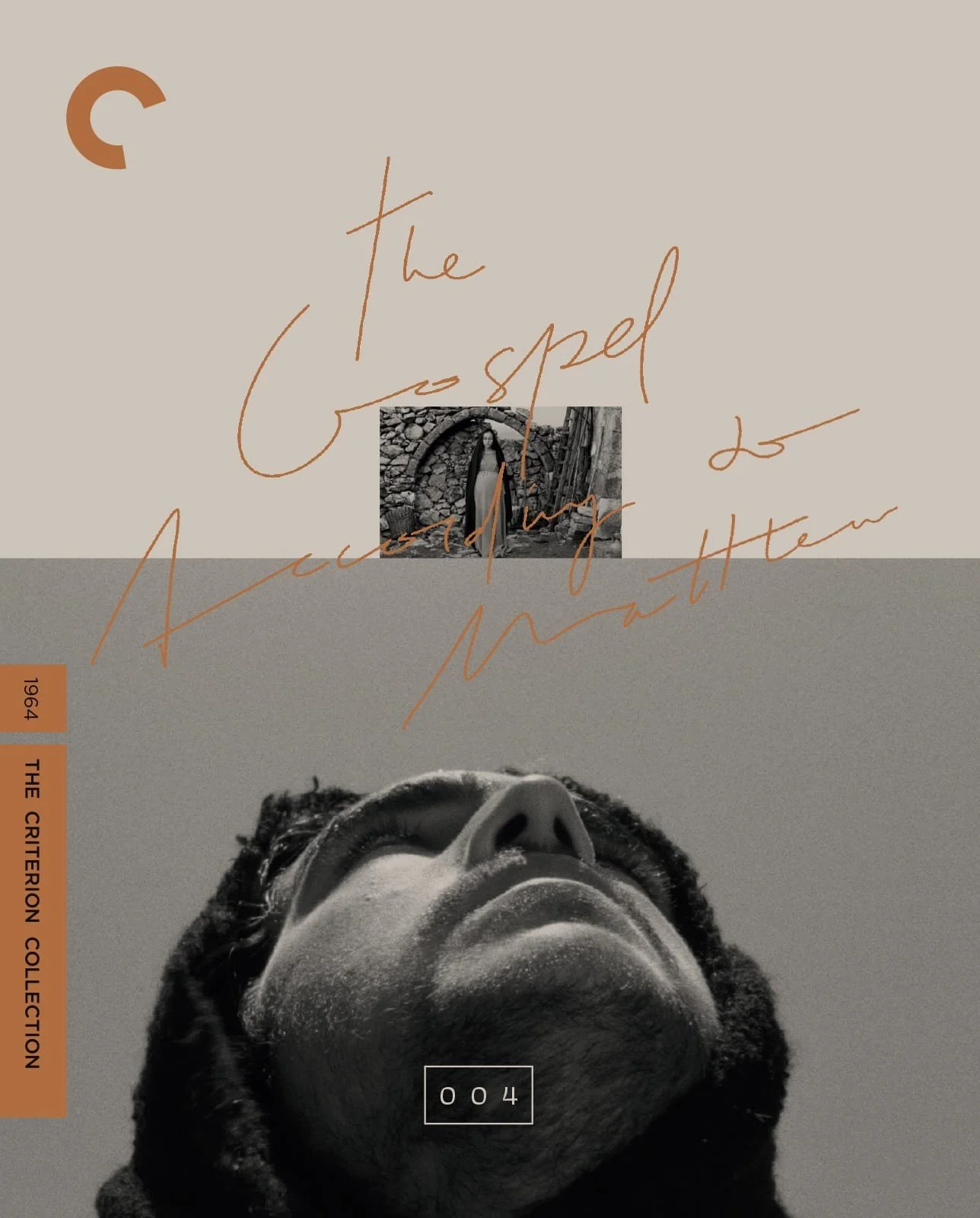

That transformation from being unnoticed to being noticed with appreciation reminds me of a recent viewing of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s increidble film: The Gospel According to St. Matthew. To my mind, it is the most poetic and sublime film ever made about the gospels, which may surprise some people: the director, Pasolini, was a confessed Marxist and atheist.

More about Pasolini’s beliefs soon. First, what do I mean by the gospels being unnoticed? I cherish the gospels, read them often, hear them at every mass, and think about their importance to my life almost daily. However, like everyone else living in a culture easily capable of diverting our attention from the heavenly to the earthly, my prayer life and my spiritual life can suffer when I let the cares of this life consume or the non-essential things of this life distract. At those unfortunate times, I might find myself listening listlessly to a Sunday homily about being a fisher of men while I more aggressively consider the Green Bay Packers chances of winning later that afternoon. That is, of course, not good. I’m not proud of these moments, but they happen. While dealing with my latest bout of spiritual laziness, I was, however, graced a remedy: I sat down one Saturday morning early, before my wife and children and the fever of life exploded awake, and I watched Passolini’s gorgeous black and white rendition of Matthew’s gospel.

The film does so much so well, but I want to focus on just a couple aspects that stood out to me: its unsentimental portrayal of the gospel and its extraordinary combination of music and visuals.

First, in contrast to many other Biblical films, where the actors appear so clean you can practically smell the shampoo, The Gospel According to St. Matthew is unafraid to portray the dust and filth of desert life. Filmed in remote areas of Southern Italy with local people hired as amateur actors, the movie helps you see the squalid living conditions and grimed faces of the people Christ preached to. Pasolini’s camera often captures the swirling desert sands, and he likes to let the camera focus on the different faces of the normal people cast as extras, which can be jarring but also engaging, at times with disturbing effect. For instance, in a scene right before King Herod’s soldiers rush to brutally slaughter all the infant sons of Bethlehem, Pasolini pans slowly from one normal looking soldier’s face to the next. The impact is disturbing because we are implicated: might any of us normal folk, if we lived during this time period, have been servile to Herod’s rule and defended that rule through violence, however extreme? If you think that is too extreme a thought, take the scene where Christ is before Pontius Pilate, which Pasolini films brilliantly.

Christ and the soldiers stand in front of Pilate, but they are in the background of the shot, while the camera wobbles a little in the foreground amongst the crowd of onlookers. Pilate’s voice can be heard but not loudly, so as viewers, we take the point-of-view of one of the guilty mob members who will call for Christ’s crucifixion. Indeed the camera remains in the crowd as the shouts cry out for Christ’s death, and we will soon watch from the crowd as Roman soldiers place the crown of thorns on his head and the cross on his back. Pasolini is defiant: we too would have abandoned Christ or took part in the mob thirsting for his death.

Pasolini’s unsentimental portrait of the gospels can also be seen in the figure of Christ. Instead of a famous and handsome Hollywood actor, Pasolini chose Enrique Irazoqui, a nineteen-year-old who had never appeared in a film. Enrique is not muscular; he is slight. He is not ugly, but he does have, jarringly for me the first time he appeared on screen, a mustache and a thick unibrow. Probably not the image most of us have when we think of Christ, but Pasolini, I believe, chose the right actor. The eyes and gaze of Enrique are fierce. In the scenes where Christ preaches the Sermon on the Mount and the other holy commands that immediately follow, Pasolini lets his camera focus just on Christ’s face as his new commandments are spoken. Christ’s eyes are black and passionate and look as if the deep inner life of his spirit is ablaze and trying to burn its intensity towards his listeners, which again, includes us, the viewers. As we hear Christ’s words so rapidly and intensely spoken, we are challenged to rid ourselves of any image of Christ as a fluffily bearded white man smiling at us to join him for some nice-guy preaching in a verdant meadow.

Besides the unsentimental portrait of the gospels, Pasolini also masterfully merges imagery and sound. Who would even think to place an American blues song in a gospel film? Pasolini did, and he did so to incredible effect. In one of my favorite scenes, a crippled man holding two long walking sticks limps and contortedly twists along a rocky path toward Jesus. Pasolini lets the moment linger so we can sympathize with the man’s pain, and to amplify his pathos, a blue’s song accompanies the shot. The song, “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” is a gospel blues song recorded by Blind Willie Johnson in 1927. It has no lyrics save for the provocative title. But its sound is incredible. Blind Willie picks and slides his guitar while moaning a haunting melody. The song doesn’t sound recorded as much as it sounds unearthed, as if the blood of martyrs has been dug up and given voice. If you close your eyes while the song plays, you can imagine walking through an early 19th century American cotton field and hearing the melodic but plaintive cries of despairing slaves.

This move by Pasolini is a stroke of genius. It helps illustrate the timeless nature of the gospel message, which is meant to urge us all to help the oppressed, the poor, and victims of any kind, in whatever time period we find ourselves in. And the entirety of Pasolini’s soundtrack is able to, whether through contemporary or classical music, find just the right notes to help viewers grasp that gospel message.

The film is powerful in other ways too. The costumes, for instance, help show the profound contrast between the religious-political elite and the poor. The temptation scene is filmed poetically in some strange, desert-volcanic, other-worldly dimension. The scene of the massacre of the holy innocents explodes our sentimental, Americana-Christmas version of the events surrounding Jesus’ birth.

I could go on.

But I also keep thinking of the man largely responsible for the film: Pasolini, a Marxist and an atheist. Interestingly, Pier Paolo Pasolini dedicated the film to Pope John XXIII. In 1962, the pope arranged a conference for non-catholic artists to dialogue with the church. Pasolini attended, and while being confined to his hotel room for a few hours, he famously read the gospels straight through. Pasolini was raised Catholic, so he presumably knew a decent amount of scripture, but this gospel-reading occasion inspired him to create The Gospel According to St. Matthew. The whole conference experience, in fact, is what inspired him to dedicate the film to the pope.

What can we make of this? A lot, I suppose. But for me, one thing stands out in particular: our beliefs are often complex. Yes, Pasolini was a Marxist. A lot of intellectuals were in the mid-twentieth century. Marxism was in vogue. Being one did not mean Pasolin was, for example, a militant Stalinist. Quite the opposite. He revered the poor and thought socialism could ease their burdens. He found the gospels inspiring because of Christ’s profound love for the poor and oppressed. Whatever one thinks of Pasolini’s political or social beliefs, one cannot jump to the conclusion that Pasolini was an evil man opposed to Western values.

Here is a brief interview with him filmed shortly after he made his gospel film:

At the end of the interview, he ignorantly rejects the idea that the gospels can be consoling, but at the beginning of the interview, he thoughtfully states that his view of the world is “not a natural or secular one…I always see things as being a bit miraculous…every object to me is a miracle…my view of the world is, in a certain way, a religious one.” We can see that his atheism is not related to a lot of the shallow atheism in today’s culture. Pasolini had his issues with organized religion, but in order to make such a sublime film about the gospels, we have to assume grace was involved in some fashion. I am reminded of a recording I listened to once about a Mozart opera. The opera expert mentioned that Mozart excelled in a variety of musical forms, even sacred music, though the expert quickly mentioned that Mozart was no more religious than he had to be for the era he lived in. That comment annoyed me. Mozart was no saint, but if we listen to his “Ave Verum Corpus” or “Vesperae Solemnes De Confessore,” we are forced to recognize that the supreme beauty of the music reflects something of Mozart’s supreme feeling for the divine. The same can be said, I think, for Pasolini. And that should humble us, especially in reference to our judgements about our fellow man, which are often dubious and shallow.

But in truth, I cannot pretend as if I know more than anyone else about Pasolini’s inner life. However, I do know that the good Lord allowed Pier Paolo Pasolini to make a wonderful film about Christ and the Gospels, and if you can make some time to watch it and if you have the right disposition, the film might, with some help from grace, do something rare for a work of art: strengthen your faith, hope, and charity.