Is the Monomyth a Myth?

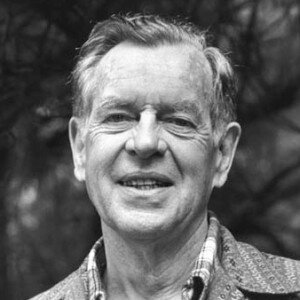

The most recent Star Wars movie has revived discussion about the franchise's supposed mythological-legendary structures, particularly regarding George Lucas’s reliance on the idea of the “monomyth” as popularized by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. I must admit that I have never found Campbell to be a very impressive intellectual. Ancient myth has long fascinated me, but the Jungian appropriation of these stories always felt like a cheap way of legitimizing that particular philosophy of the human mind. At its best, the monomyth feels like a curious theory of comparative religion; at its worst, it may be an excuse Dr. Campbell concocted to justify his apostasy from the Catholic Faith. Or maybe it’s just academic fraud.

Let’s begin!

Campbell, like so many Freudians, Jungians, and comparative religionists before him, reduces religion to a set of taboos concocted via the irrational movements of the unconscious interacting with waking society. Similarly, he believes that “myth” is an outworking of individual dreams as shared between dreamers and elaborated upon over time. The “monomyth” is Campbell’s attempt at tossing all heroic stories together to find their common core.

This supposed common core is surprisingly complicated. Mircea Eliade’s description of the heroic trope is much simpler and comprehensible, comparing it to the solar cycle: “Like the sun, he fights darkness, descends into the realm of death and emerges victorious” (The Sacred and the Profane, 157-8). Campbell is not content with something so clean, and provides an elaborate, seventeen-step framework that can supposedly be found in heroic myths throughout the world:

Departure (i. The Call to Adventure, ii. Refusal of the Call, iii. Supernatural Aid, iv. Crossing the Threshold, v. Belly of the Whale)

Initiation (vi. The Road of Trials, vii. The Meeting with the Goddess, viii. Woman as Temptress, ix. Atonement with the Father, x. Apotheosis, xi. The Ultimate Boon)

Return (xii. Refusal of the Return, xiii. The Magic Flight, xiv. Rescue from Without, xv. The Crossing of the Return Threshold, xvi. Master of Two Worlds, xvii. Freedom to Live)

The problem with this 17-Step Program to Heroic Success is that it cannot really be found in any heroic myths in its fullness before Campbell’s book. Examples from specific steps can be found in stories throughout the world, but even Campbell seems unable to provide even one example of a heroic story that uses this entire framework. Many of the stories Campbell references are merely useful for one or two steps, and it’s only by referencing larger mythological libraries (like the total mythic tradition of the Greeks) that he can find enough material to fill in the gaps.

In other words, Campbell invented the seventeen-step framework and selectively picked fragments from many myths and legends to fit into his preconceived model. He does come close to admitting this deficiency a few times, for instance:

Many tales isolate and greatly enlarge upon one or two of the typical elements of the full cycle (test motif, flight motif, abduction of the bride), others string a number of independent cycles into a single series (as in the Odyssey). Differing characters or episodes can become fused, or a single element can reduplicate itself and reappear under many changes. (Hero, 212)

That fact is that myths, even heroic myths, are far less neat and structured than the monomyth theory would lead one to believe. The search for the monomyth is something like the physicist’s search for the Grand Unified Theory, and just as successful. Describing the “hero’s journey” in any but the broadest terms is bound to lead to pedantry and logical fallacies, carts before horses and tails wagging dogs.

The malign influence that the monomyth has had on storytelling since Campbell is obvious from the legion of novelists and screenwriters who use his framework as a paint-by-numbers outline. It discourages the storyteller from observing human psychology and behavior as it occurs around him, and from delving deeply into his own soul to understand the mystery of humanity.

Common motifs between cultures, religions, and poetic traditions are always interesting to note. One must, however, fight the temptation to make too much out of them. One cannot claim that all myths or all religions are basically the same without immediately needing to fend off a thousand exceptions. Too many scholars respond to that call for reality with outright refusal.