Friday Links

October 3, 2025

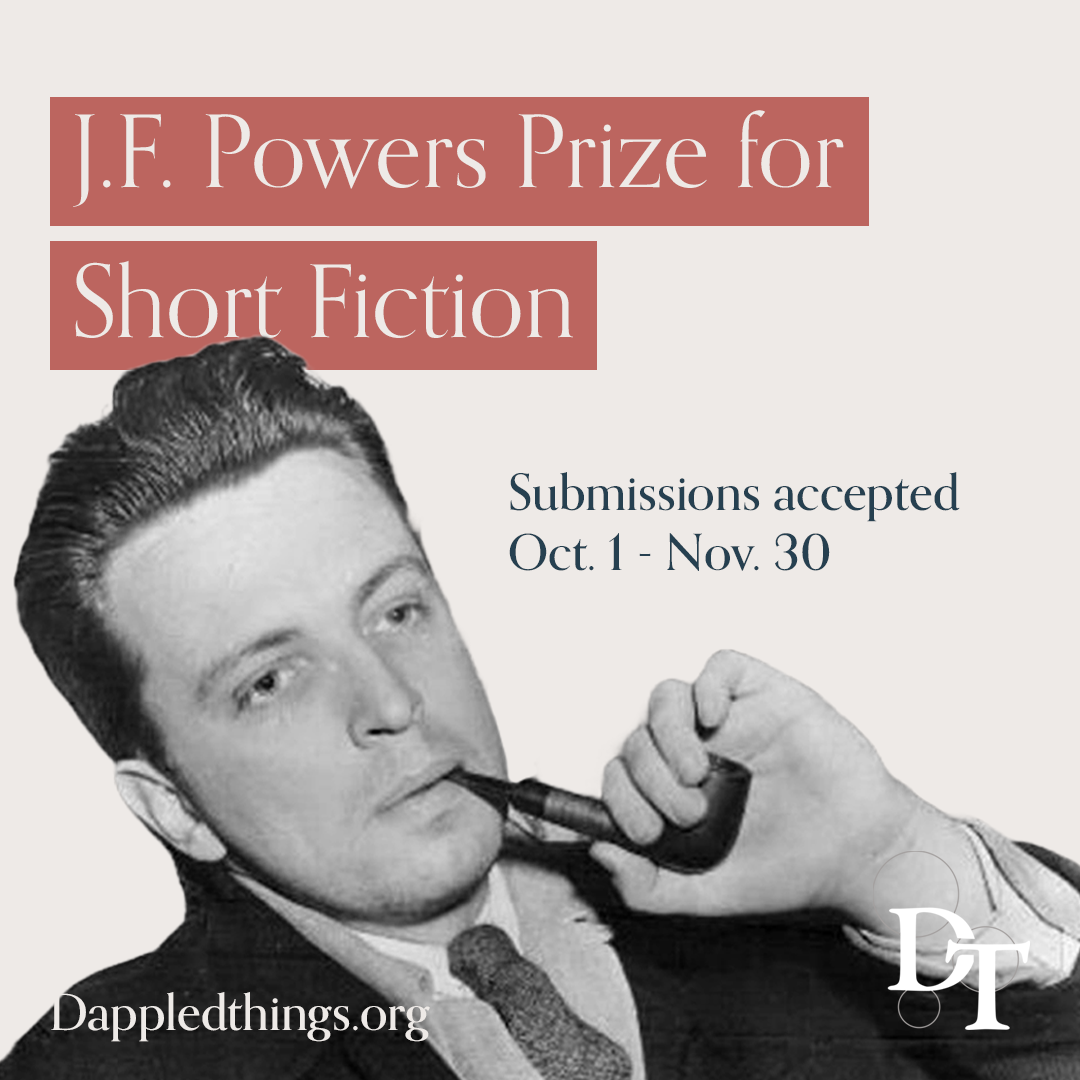

2025 J.F. Powers Prize for Short Fiction

He’s Christian. In Nigeria, That Meant Torture and Prison.

E, J. Hutchinson on how “Mature Poets Steal”?: Dylan and Eliot

Joshua Whitfield: Why Sunday Matters: The Return to This-Is-Good Goodness

The Words Beneath the Rocks: Robert Redford's A River Runs Through It

Bring on the Joy with Shemaiah Gonzalez!

2025 J.F. Powers Prize for Short Fiction

The editors of Dappled Things are pleased to announce that submissions for this year’s J.F. Powers Prize for Short Fiction are now open. Named after one of the greatest writers of the 20th century Catholic literary renaissance–often called a writer’s writer–the contest aims to honor his legacy by awarding stories that, like the priests he wrote about in his fiction, have “one foot in this world and one in the next.” The contest awards prizes of $700 to the winner, $300 to its runner up, and publication for any additional honorable mentions at the discretion of the editors.

Submissions will close on November 30, 2025.

He’s Christian. In Nigeria, That Meant Torture and Prison.

JC: What would you say to others who might one day face similar persecution for their faith?

David: They should trust in the Lord because the Lord is able to do all things. They should not be afraid or doubtful. Christ did not find it easy when he was here on Earth; so it is also with us—Christians will not find it easy. This world does not belong to us. The Earth is not our home. We have an eternal home in heaven.

E, J. Hutchinson on how “Mature Poets Steal”?: Dylan and Eliot

Every verse of that song, later unforgettably covered by The Byrds, ends like this:

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that nowWhere did Dylan get the idea for that? Did he make it up? Heylin connects Dylan’s earlier version of these lines (“Ah, but that’s when I was older, I’m growin’ younger now”) to the old Scottish folk song “Young but Daily Growin” (also know as “The Trees They Grow So High“).[2] Maybe, though that wouldn’t apply so well to the final form of the lyrics; and in that song, the man does not grow younger in any case, but the opposite. He’s young, and growing older. That is the customary order of things. It’s the reversal of the normal order that is surprising in Dylan’s song.

Joshua Whitfield: Why Sunday Matters: The Return to This-Is-Good Goodness

But, of course, it is not that simple. I mean, it is that simple, but sin has ruined it, rendered everything difficult, complicated things. You know the story; you know your story. The Fall, your fall; the world, the flesh, the devil, and you; and me too. You know what I mean. That this-is-good goodness is at best fleeting; it is not at all the normal constitution of our existence, or the normal experience of creation, or of nature, or of our fellow human beings. The Bible is as much a story of humanity’s descent into violence and chaos as it is a story of salvation. The first homicide is found in the fourth chapter of Genesis; in the sixth chapter, just before the flood, it says, “And he was sorry that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart.” Between the goodness of Eden and us is all of that, all of history’s evils and tragedies and sins. What St. Augustine called the “wear and tear of the world” is what prevents most of us from knowing what the Sabbath feels like, that this-is-good goodness. It is what makes such goodness a mere memory, something mostly for mystics, an unnerving longing, most of us most of the time discontented with ourselves and with the world around us.

Samuel D. Rocha on The Words Beneath the Rocks: Robert Redford’s A River Runs Through It

Robert Redford recently passed away, as you probably heard. He made or starred in three of my favorite films (two of which are based on two of my favorite books): Out of Africa, The Natural, and A River Runs Through It. Samuel Rocha writes about the third in Church Life Journal. The film and the novella are luminous:

Robert Redford’s 1992 film adaptation of Norman Maclean’s 1976 novella, A River Runs Through It, is a cinematic work of literary interpretation. Redford takes no serious departures from the text, allowing the narrator’s authorial voice to animate the work. The film, like the book, is a family story about life. It is not a manual on how to live so much as a study of life’s significance and meaning, even its mystery, and above all, its tragedy. It is also responsible for popularizing fly fishing almost unintentionally.

Bring on the Joy with Shemaiah Gonzalez!

Living Joy does not mean a life without sorrow or pain. It does mean living in hope. In her new book, Undaunted Joy: The Revolutionary Act of Cultivating Delight, Shemaiah Gonzalez encourages finding joy in the small things in life. It’s a good practice for gratitude and being light in dark and distracting times. Based in Seattle, Gonzalez talks with Kathryn Jean Lopez about finding the joys in Costco, naps, and the much more enduring things.